International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES)[1] from Ljubljana, Slovenia, regularly analyses developments in the Middle East, Balkans and around the world. Dr Maria Smotrytska is a senior research sinologist, specialized in the investment policy of China. In her comprehensive analysis entitled “IFIMES for the Global Greening Economy (A Brief Impact Study)” she emphasizes the importance of the largest land mass of the globe - Eurasia and transport logistics through it and analyzes three possible ways of developing Eurasian transshipment lines in accordance with green standards.

International Politics & Economics specialist

As the entire globe struggles to restructure and regroup towards the greener economy and to de-acidify the oceans, air and our overall socio-political conduct, International Institute for Middle-East and Balkan Studies - IFIMES is taking its own share of planetary responsibility. Institute is an important facilitator, an indispensable political backchannel, clearing house and meeting point. Its bold presence in the United Nations and other international FORAs, along with its field presence in Europe, America, Middle East and Asia gives it additional frame and content, say and its amplified outreach.

Hereby presented mini study of the Institute’s is primarily aimed at national subnational and supranational decides-making levels, and should be understood as a policy orientation, tentative road-map for the urgent global greenification.

* * * * * * *

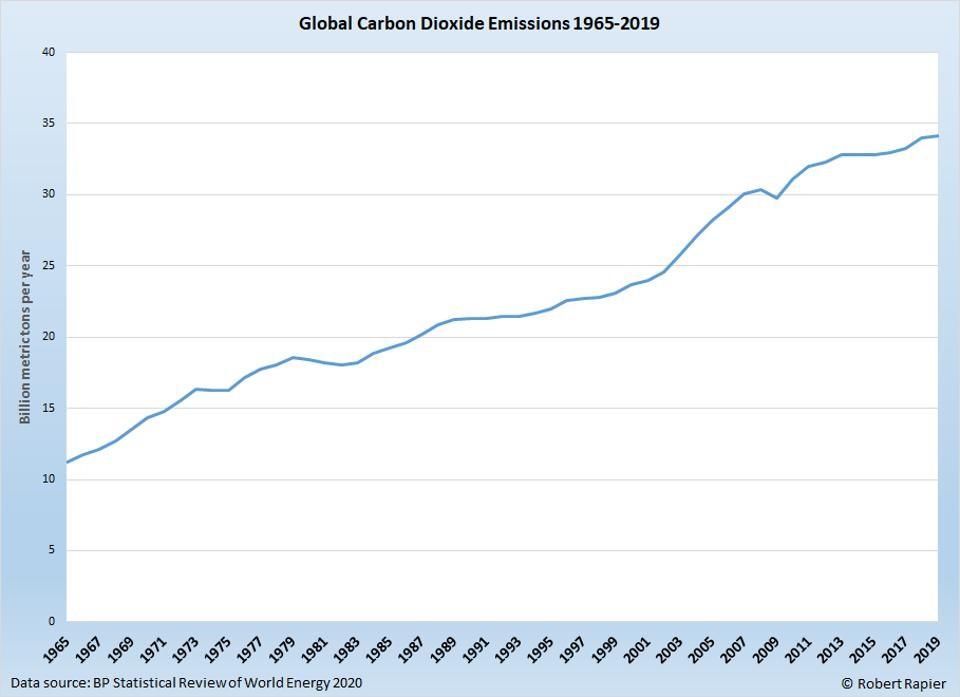

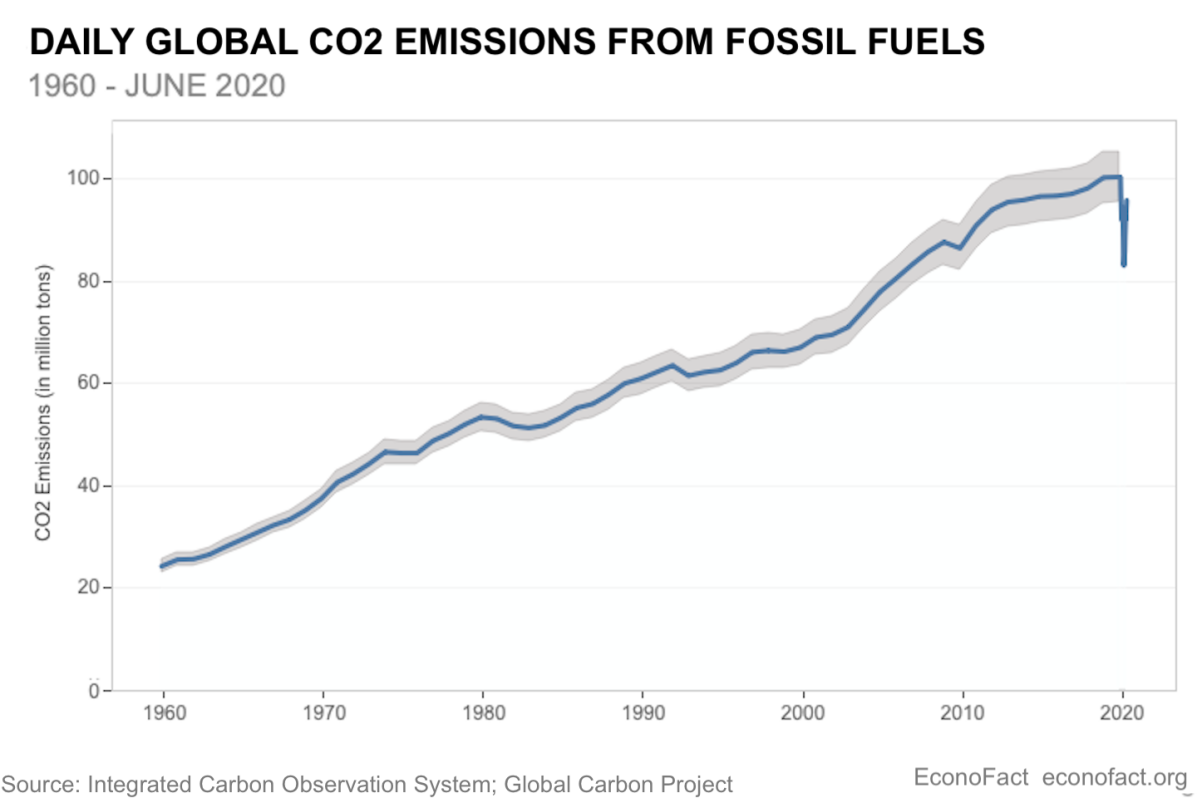

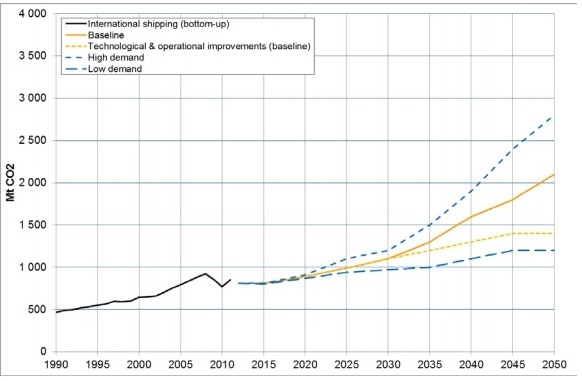

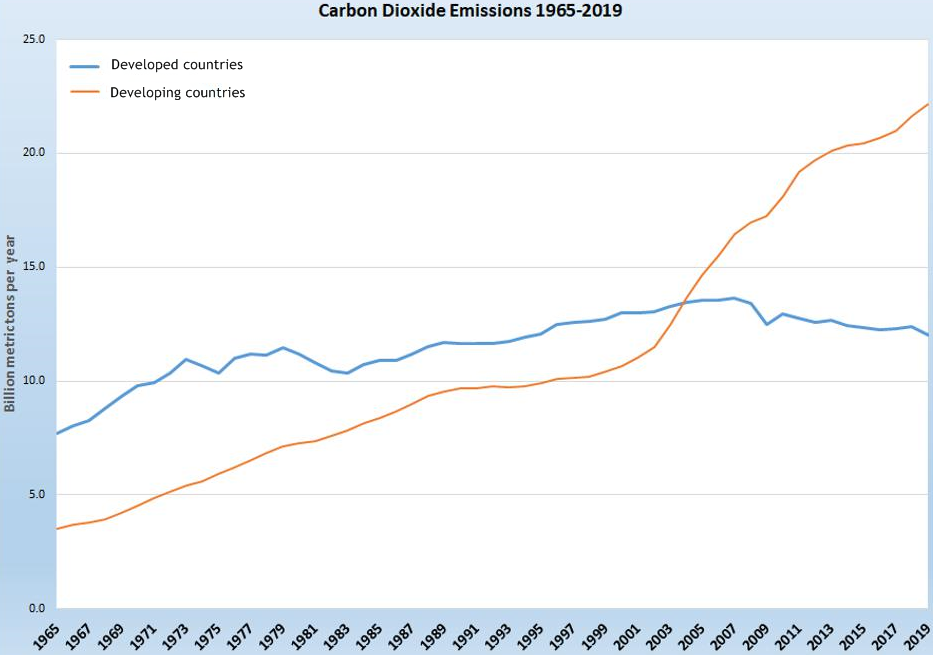

In 2019, when carbon dioxide emissions reached an all-time global high for the fourth consecutive year, it became clear that a new strategy for developing transport systems and economies needs to be implemented (See Figure 1). Despite the fact that, because of the Covid–19 pandemic, emissions are almost certain to decline for 2020 (See Figure 2) , in a longer term, it’s going to require more phasing out of coal, and continued exponential growth in the adoption of renewable energy.

Figure 1.Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions 1965–2019

Source : BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020

Figure 2.Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions 1960–2020

Source : Integrated Carbon Observation System, Global Carbon Project, 2020

Today the whole world is aware of the global problem of climate change and accelerated warming. Due to the increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases and harmful emissions into the atmosphere, this problem is getting worse every year. Air pollution occurs due to the development of industry, increased transport, and overall economic growth in countries around the world.

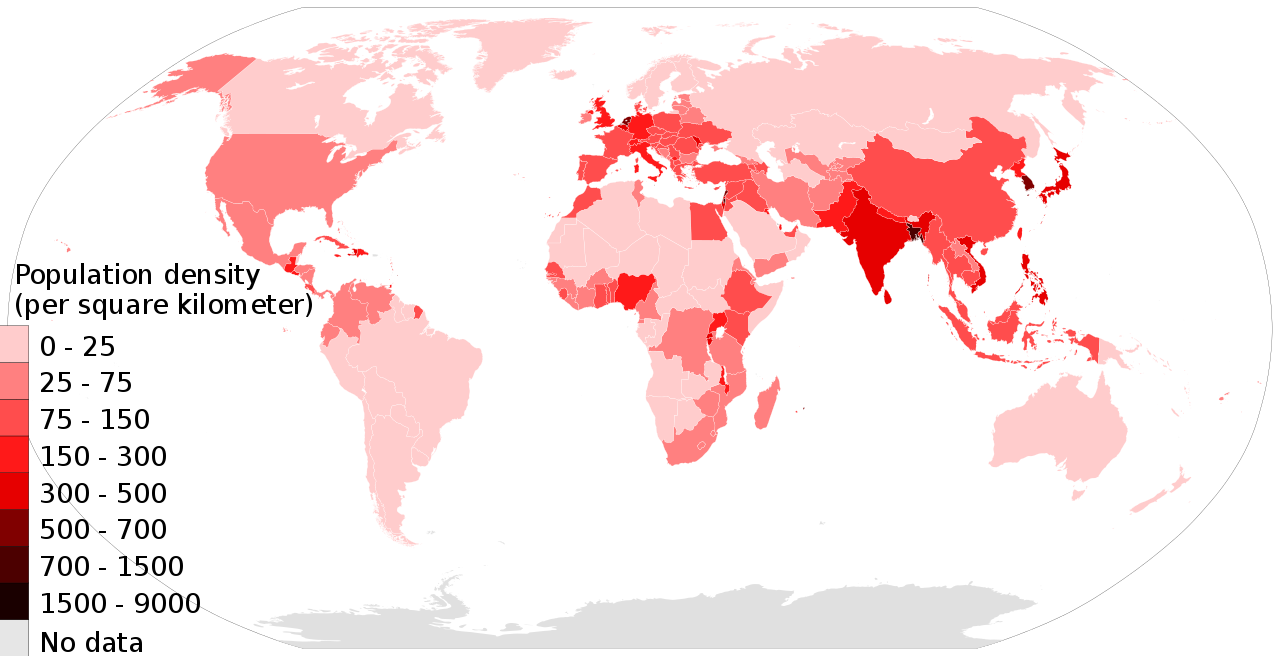

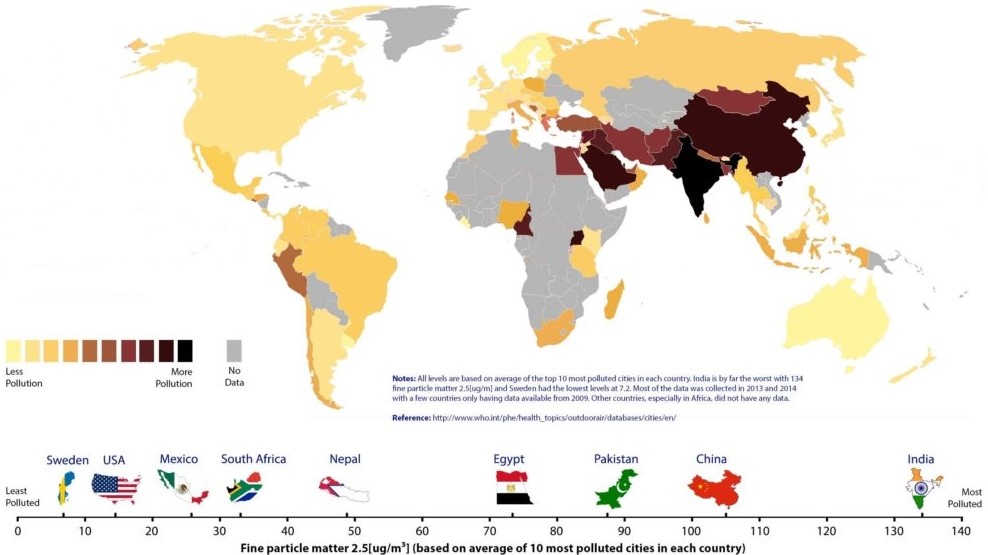

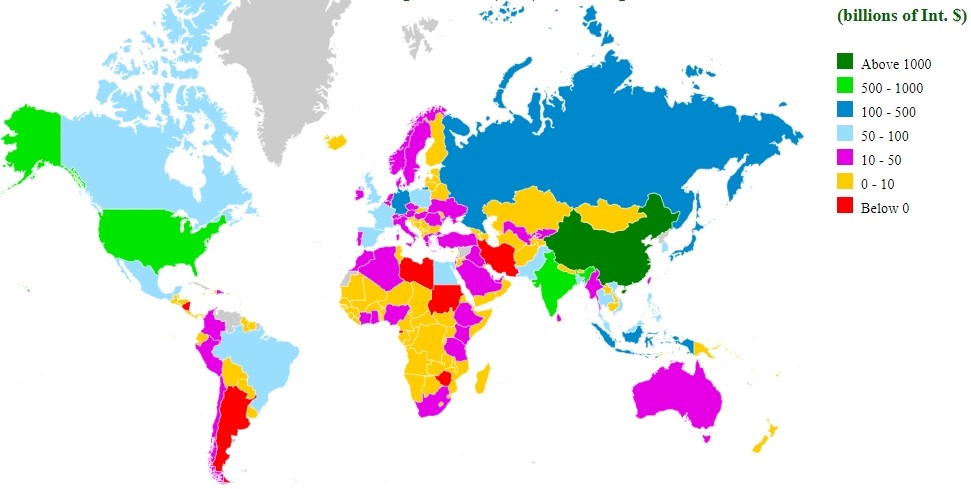

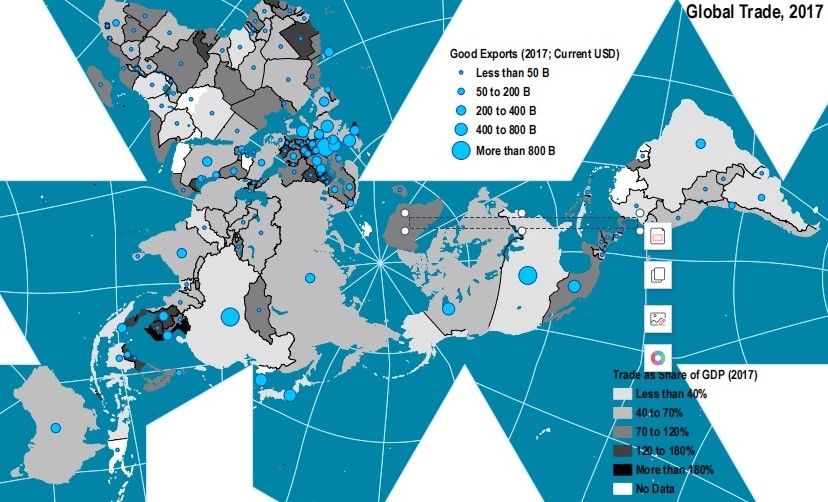

Thinking on the question how we can answer the fundamental challenge of global warming, we should understand that the most inhabitant part of the world and the largest landmass of the Globe is Eurasia (See Figure 3). Thus, it is the biggest producer of CO2 and, hence, the most polutted part of the world (See Figure 4). Also important to underline that the biggest countries-producers (Far East) and countries-consumers (West Europe), producingthe biggest economic output (See Figure 5), are located on the edge of the Eurasia. These countries, which are states of G-7 (Atlantic states and other European countries) and other advanced OECD economies (See Figure 6), drive world’s economies and may play crucial role in improving ecology and environmental standards.

Figure 3. World’s population dentisy (per square kilometer)

Source : WHO, 2019

Figure 4. Global pollution level

Source: WHO, 2019

Figure 5. Global GDP Purchasing Power Parity

Source : International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook, 2019

Figure 6. Global Trade, 2017

Source : The World Bank, 2017

Transportation logistics between Far East and Western Europe is vital for world’s economic development, but today we do not have reliable technologies and transport lines. Due to this it is necessary to think on few aspects, which may determine the development of environmental friendly economies in future:

- reliable transportation (safe and environmentally friendly);

- cheapest modes and transshipment lines;

- fastest modes of transportation

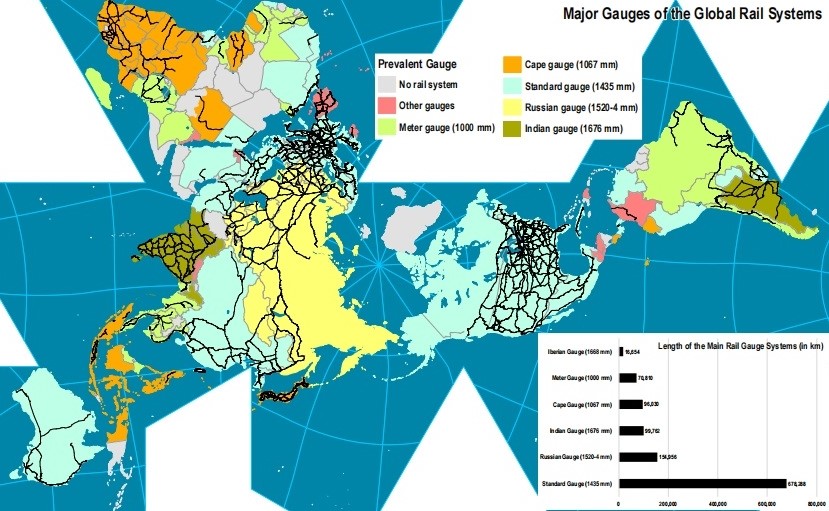

The most reliable mode of the transportation is railway.Land railways were chosen as the main export industry, which can become the engine of economic development of many transportation initiatives (TEN-T, BRI, TRACERA, etc.) (See Figure 7). It can be seen that as with the Japanese concept of ‘Flying geese’, “railways initiatives” are followed by hardware, software manufacturers, engineering and other service providers, as well as banks, insurance and other companies.

Construction of new highways, railways, gas and oil pipelines (in other words Green (land) shipping line) can also make the environmental situation in cities located along transport routes worse, as emissions from transport pollute the air and lead to an increase in the population's morbidity. Based on this, it can be argued that the environmental factor becomes an important argument in favor of rail transport compared to auto.

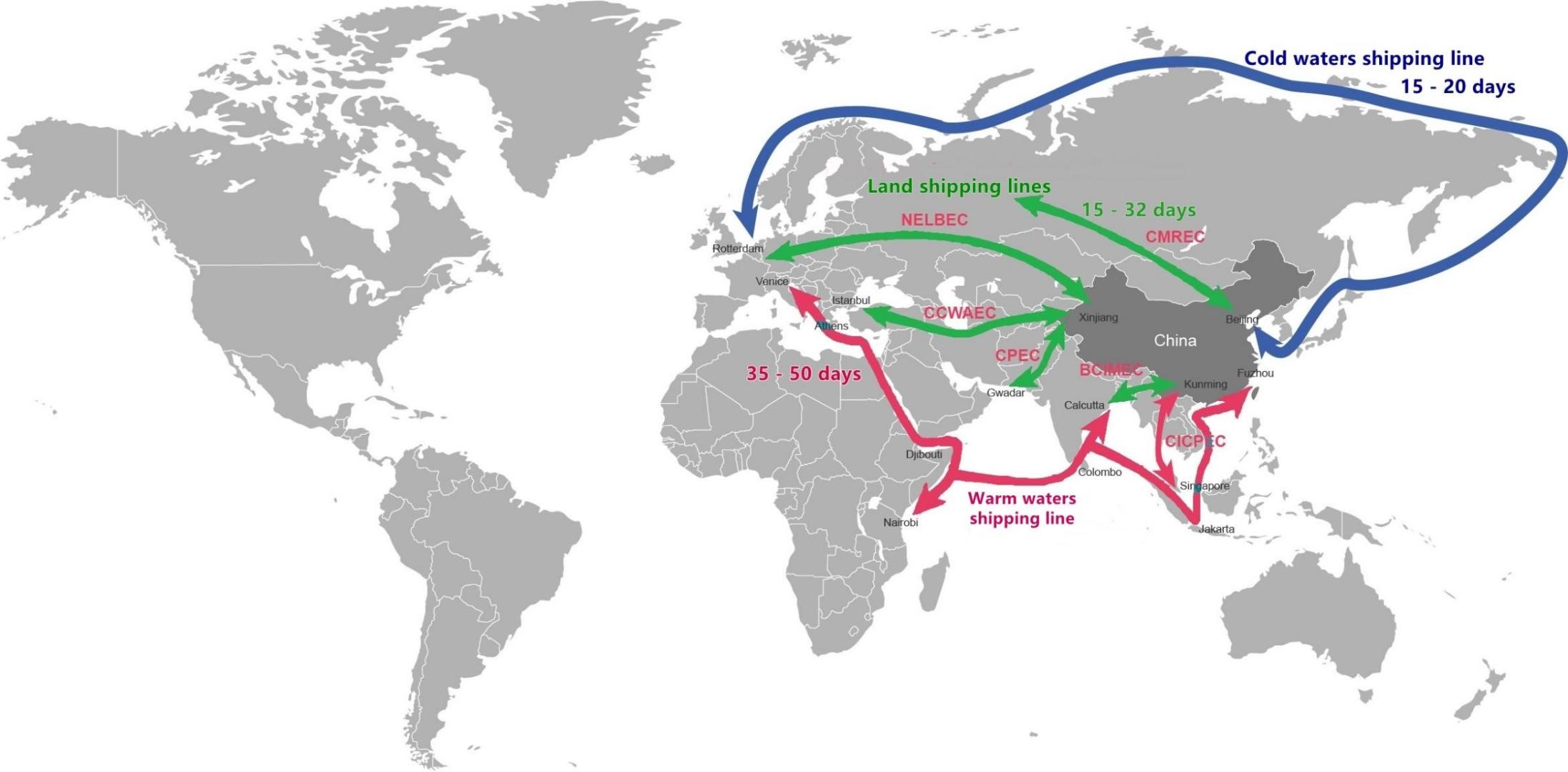

When comparing cargo transportation from the Far East by sea and by rail, the delivery time is often the key argument in favor of the railway. At the same time, the amount of 14–15 days is often mentioned. In practice, it takes longer: 42–46 days by sea, 28–32 by rail, 6 days by plane and 4 days by roads. This difference in numbers is caused by the need to form a train, delays at some stations, etc (See Figure 8).

Figure 7. Major Gauges of Global Rail Systems

Source : CIA World Fact Book, 2019

Figure 8. Transshipment lines from Far East to Western Europe

Source : EDB, 2019

Thus, railway container transport has certain advantages (compared to maritime transport) in the following areas: speed (timeframe), regularity (rhythmicity), reliability (guaranteed on-schedule delivery and cargo preservation) and the ability to deliver the cargo to any destination.

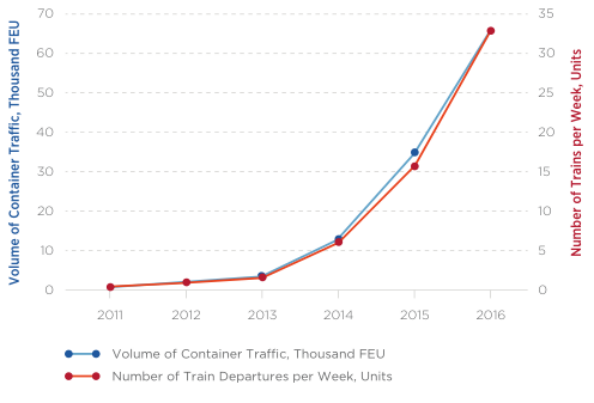

Analysts predict that in the next two or three years, all regular trains from Far East that are “placed on track” will be fully loaded. According to estimates, “convenience” elasticity of demand (“convenience” including promptness, regularity and precision of delivery) in railway container services between Far East Asia and West Europe, stands at 98%: in 2011–2016, the number of weekly train departures and the volume of container traffic have been growing virtually at the same rate (See Figure 9).

Figure 9. Changes in Container Train’s Frequency of Departure and Volume of Freight Traffic along Eurasian transshipment routes, 2011–2016

Source : Eurasian Development Bank, Center of Integration studies, 2018

Thus, strict adherence to railway schedules (99.7% of all container trains running along Far East – West Europe routes complete their journeys on schedule) and delivery times approximately one-third of what is offered by maritime transport, guarantee a wide margin of “convenience”.

It is anticipated that railway container traffic between the West Europe and Far East (transiting through the Eurasia) will increase. But to attract additional freight traffic, Eurasian states need to further expand their transport infrastructure and remove a number of barriers. There has been a considerable increase in railway container traffic from the West Europe and Far East, from 1,300 TEU in 2010 to more than 50,000 TEU in 2016. Between 2010 – 2016, transit container traffic from the Far East to West Europe increased from 5,600 TEU to almost 100,000 TEU. At the end of 2017, the volume of transit container traffic across the Eurasia along the Eurasian transshipment routes reached 262,000 TEU, exceeding the 2016 value by a factor of 1.8.

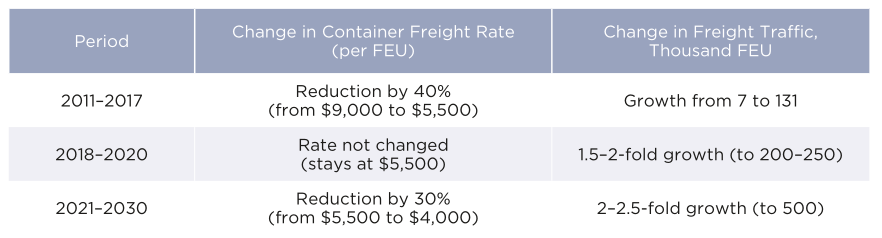

Thus, it is estimated that the container traffic increase from 200–250,000 FEU in 2020 to 500,000 FEU by 2030, is possibly subject to further reduction of the through freight rate by $1,500 per FEU (from $5,500 per FEU to $4,000 per FEU) (See Table 1).

Table 1. Impact of Railway Container Freight Rates on Container Traffic

Source : Eurasian Development Bank, Centre for Integration Studies, 2018

According to estimates, if current through freight rates are preserved, the Far East – West Europe container traffic growth potential generated by the margin of “convenience” (promptness, regularity and precision of delivery) is far from exhausted. By 2025, it may produce a manifold increase in the number of container trains and total volume of container traffic (to reach 200–250,000 FEU), with the number of train departures per week (regularity) going up by a factor of three (to about 100 per week)

The so-called high-speed railway diplomacy ensures the development of the transport and logistics sector of the entire continent. However, how energy-safe is it?

Although the overall adverse impact of rail transport on the environment is less than that of auto transport, diesel locomotives with diesel power plants have a negative impact on the atmosphere, since the exhaust gases contain hydrocarbons, carbon oxides, nitrogen, sulfur, and various solid pollutants.

Analyzing and estimating of the CO² emissions directly resulting from transport between Far East and the Western Europe by air, sea and rail, it has been assumed that carrying a TEU by container ship results in emissions of around 0.5 tonnes of CO2. These emissions might fall in future, if the average value of goods sent by sea fell, and if this resulted in ships sailing at lower and more efficient speeds.

It has been also assumed that carrying a TEU using diesel trains would result in emissions of around 0.7 tonnes of CO2. However, the emissions from electric trains could be lower, possibly even falling to zero, if they were powered entirely by renewable sources. Over time, this may in principle become possible if electrification, and the use of renewable sources of energy, becomes more extensive. This would, however, depend primarily on the provision of electrification throughout the routes used by transport systems –related trade on the railways of the whole Eurasia.

On the other hand, a range of estimates of the average cost per tonne-kilometre of air freight can be found. The United Kingdom’s Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) estimates that air freight on long haul flights results in emissions of 630 grams of CO2 per tonne-kilometre. This implies that five tonnes of air freight flying around 8,000 kilometers between Far East and the Western Europe would result in emissions of around 25 tonnes of CO2, compared with an estimated 0.7 tonnes if carried by dieseltrain.

In summary, every TEU transferred from air to rail would reduce CO² emissions by nearly 25 tonnes, and every TEU transferred from shipping to rail might increase CO2 emissions by at most 0.2 tonnes, but could reduce or eliminate CO2 emissions if a significant portion of the journey were powered by renewable energy sources. This suggests that, if assessed by the CO2 emissions resulting from transport between the Far East and Europe, the Eurasian transshipment lines is likely to be beneficial to theenvironment.

While in theory, the implementation of railway electrification and the use of renewable energy sources can reduce CO2 emissions, perhaps even to zero, in practice this process can take decades of years that our planet is unlikely to have.

This fact makes humanity think about other possible modes of transportation that can benefit both in “convenience” (including speed, regularity and accuracy of delivery), and in reducing CO2 emissions.

In accordance with the Figure 3 it can be seen that for now the most beneficially is the land (green) shipping line. Due to the fact that Maritime (warm waters – red) transport delivery speeds remain rather low (including those of modern container ships). Vessels travelling along the Eurasian transshipment route run at 20 – 25 knots, while average total travel time, including the Suez Canal passage and port calls, is 35 – 45 days. Besides, there always remains the risk of delays for natural and other reasons (such as waiting for loading at the port of departure). Despite this, the regularity (rhythmicity) of maritime container traffic between the ports of the Far East and the Western Europe is rather high. For example, Maersk Line alone makes six runs per week. However, when using the sea route to carry containers between the Far East and the Western Europe, one has to take into account not only the actual travel time (4 – 6 weeks), but also the time required for consolidation of cargoes in ports (about 1 week).

It is estimated that cargo, currently carried by maritime and air (white shipping line) modes between Europe and the Far East, will in future shift to rail as a result of improved services attributed to the Eurasian transshipment lines. It is indicated that around 2.5 million TEUs could transfer to rail from maritime transport, and 0.5 million from air transport, by 2040, which is equivalent to 50 to 60 additional trains daily, or 2 to 3 trains per hour, in each direction.

Currently about 98% of mutual Far East – West Europe deliveries are made by maritime transport, with aviation transport and railway transport accounting for 1.5–2% and 0.5–1%, respectively. Approximately 80% of Far East – West Europe cargoes are carried in containers, including about 90% of cargoes brought to West Europe from the Far East (imports) and 70–75% of cargoes carried from the West Europe to the Far East (exports).

This data shows that investment in rail infrastructure are leading to rail being a viable alternative to both sea and air for trade between the Far East and Europe.

In regards with the environmental issue, this means that if maritime services lose their most time-sensitive cargo to rail, they might in practice sail their ships slower, extending transit times but reducing fuel costs and hence prices, and decreased CO² emissions.

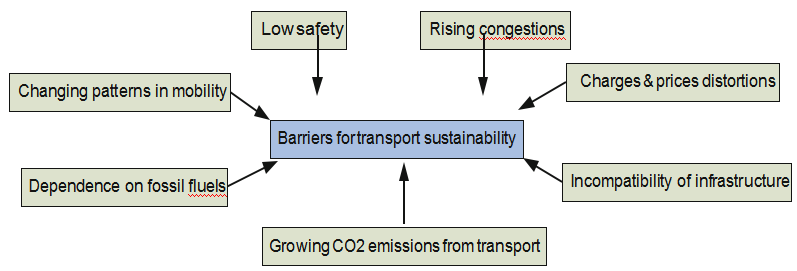

The warm waters shipping line from Far East and the Western Europe for the delivery of goods to the Balkan Peninsula, which lies at the intersection of transit communications in Europe, Asia and Africa, today has great logistics prospects. Currently, 80% of cargo goes through the Atlantic ocean to the ports of Northern Europe (See Figure 8). The warm waters shipping line through the Arabian sea and the Suez Canal to the Balkans will reduce the transport time by 7 – 10 days: this is so far the shortest sea route from Far East and the Western Europe (however, to do this, CEE needs to build transport infrastructure, which the region has a huge need for. This is especially true for the Balkan Peninsula, which has entered a period of stable development after riots and wars that caused serious damage to infrastructure) (See Figure 10)

Figure 10. Barriers for transport sustainability

Source : Sustainable Transport. New Trends and Business Practices, 2019

But being the cheapest so far mode of transportation, warm waters transshipment linespresent big dangers, which are making them rather vulnerable and less stable than railway road.

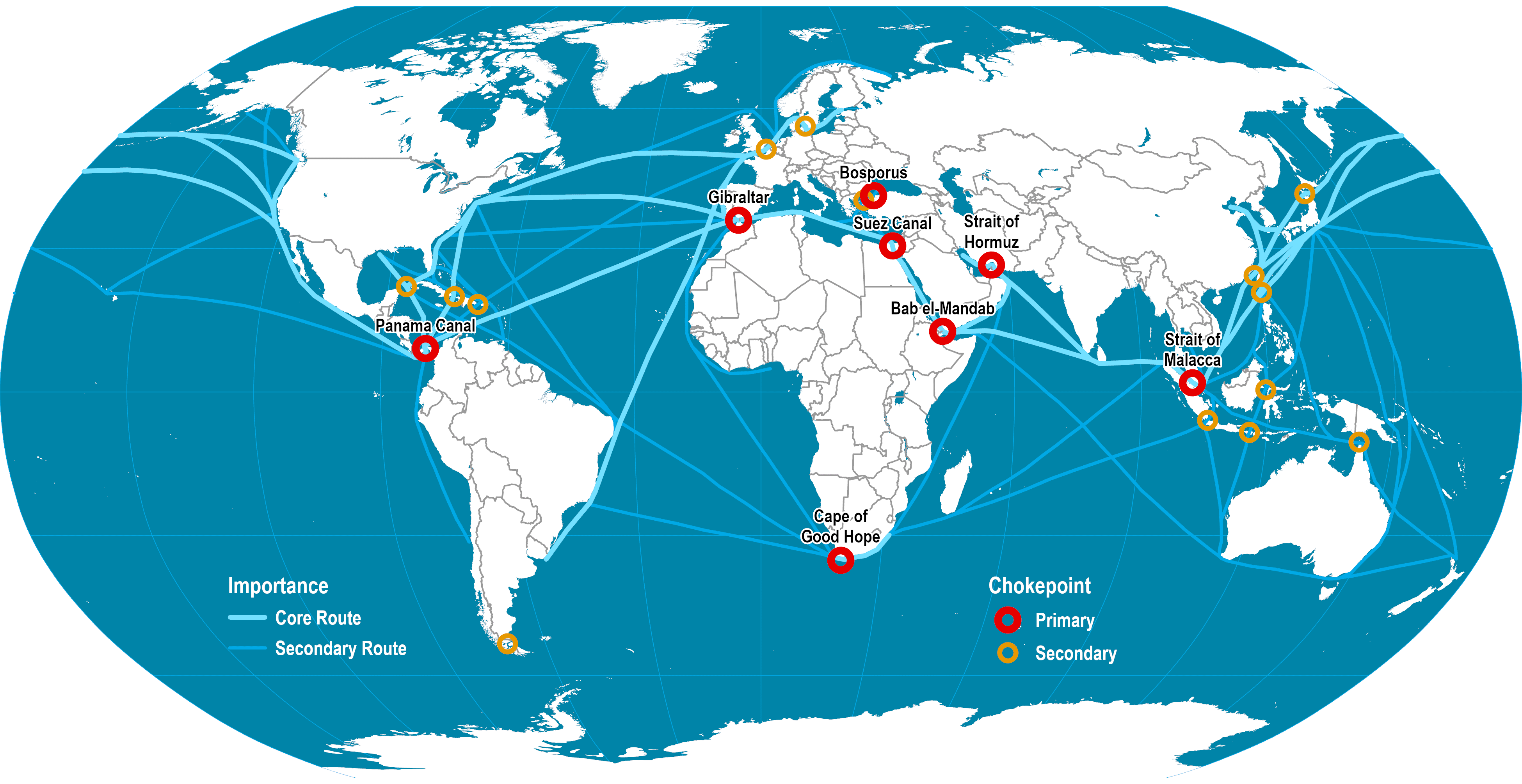

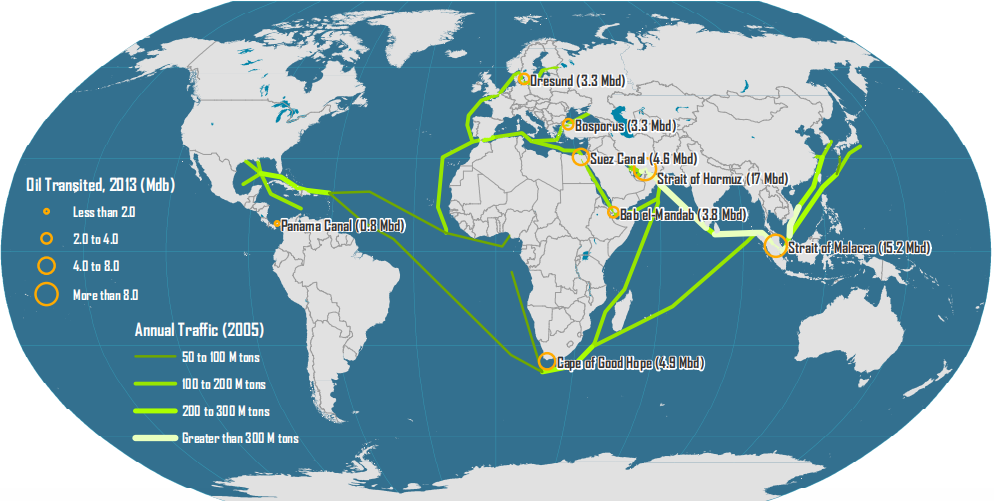

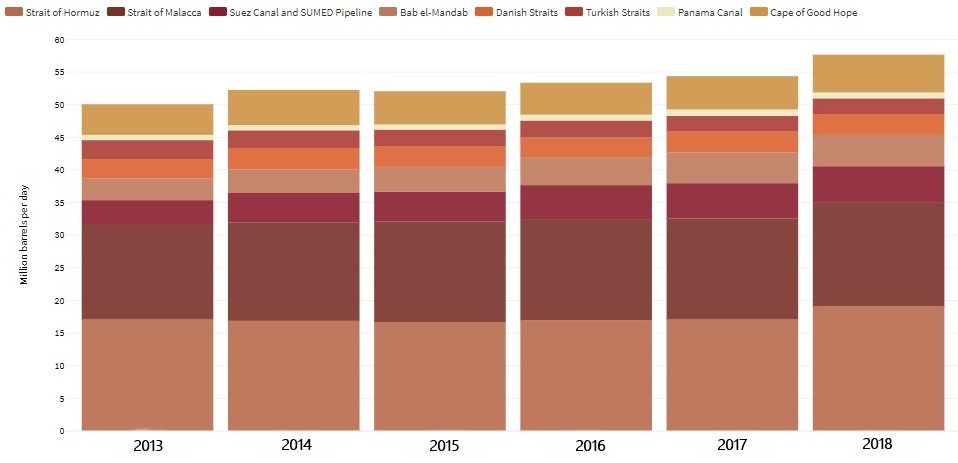

The low cost and the higher degree of safety compared to transportation by land, has led to an increased number of commercial fleets over the past few decades. Thus, the biggest challenge is the problem of the high level of congestion in warm waters. Currently there are several maritime zones of bottlenecks (see Figure 11):

Figure 11. Main maritime shipping routes

Source :Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

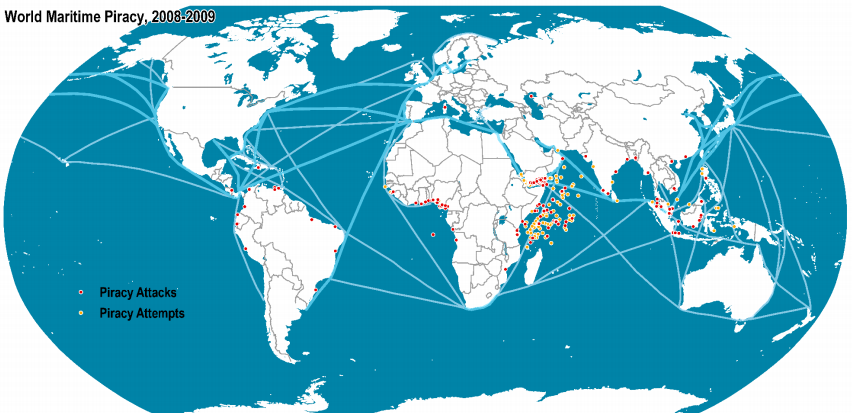

- The Straits of Malacca and Singapore (SOMS) is the second most important global chokepoint, with over 16 million barrels per day (120,000 ships passes this route each year). It is a vital strategic region for seaborne trade, since it is the shortest route between the Pacific and Indian Oceans (see Figure 12). This narrow, 550-mile strait is also a major route for oil transportation, hence creating a danger of potential oil spills or collisions, significantly damaging the biodiversity and the marine environment. Moreover the SOMS is polluted not only by the oil and ships, but also by enormous noise, influencing the marine bio-life. The transshipment line in addition is not considered as a safe pass, since it is beset with challenges, natural (during frequent squalls from the Indian Ocean, visibility can decrease considerably to make it difficult for mariners to navigate) and man-made (piracy) (See Figure 13).

- The Phillips Channel in the Singapore Strait is just 2.7km wide making it another maritime zone of bottlenecks and potential oil spills (See Figure 12). With so many vessels in the crowded Singapore Strait, there is often an increase of incidents.

Figure 12.The Straits of Malacca and Singapore (The Phillips Channel)

Source : Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

Figure 13. World Maritime piracy, 2008–2009

Source : ICC International Maritime Bureau, 2009

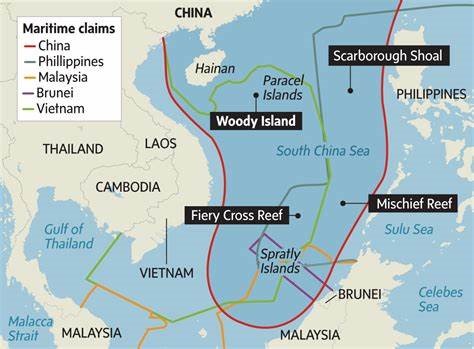

- From the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, ships make their way to the South China Sea, another zone of unstable waters in the South-East of the Indian ocean (See Figure 14). The South China Sea is a prominent shipping passage with $5.3 trillion (nearly one-third of all global maritime trade) worth of trade cruising through its waters every year. Since this zone has emerged as one of the most dangerous flashpoints in the Indo-Pacific over the last decade, the transshipment here is rather unsafe, not mentioning the ecological disasters which are emergenining currently there.

Figure 14. The confict zones of the South China Sea

Source :Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

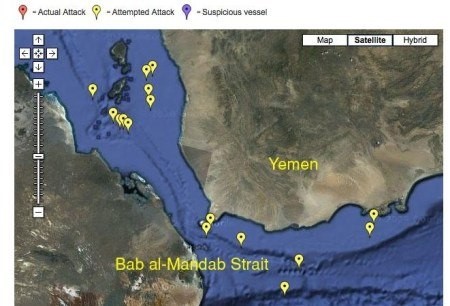

- The Strait of Bab-El-Mandeb, one of the World’s Most Dangerous Straits (situated in the high conflict zone between Yemen and Somalia), is also the shortest trade route between the Mediterranean region, the Indian Ocean (see Figure 15), and the rest of East Asia. Oil-rich Arabian Gulf nations rely heavily on it: approximately 57 giant oil vessels from these countries pass through the strait each day, over 21,000 each year (See Figure 16). This fact makes the straight not only the zone of interests of main powers (and hence high tension in the region), but a big threat to the environment (oil spills).

Figure 15.The Strait of Bab-El-Mandeb

Source:Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

Figure 16. Major oil flows and chokepoints

Source : US Energy Information Administration, 2018

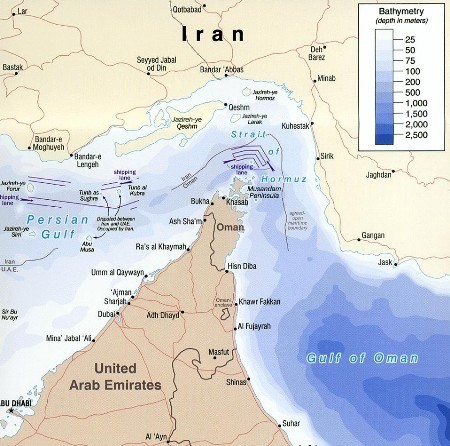

- The Strait of Hormuz is a strategically important strait or narrow strip of water that links the Persian Gulf with the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman (See Figure 17). As one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, is also one of the most essential ones, due to the amount of oil tankers that navigate these waters on a daily basis. Around one third of the world’s oil is transported through this strait, making it essential not only for trade, but for the global economy as a whole (See Figure 16). The same fact is making this route one of the most dangerous to the environment, considering existent oil spills or collisions.

Figure 17. The Strait of Hormuz

Source: Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

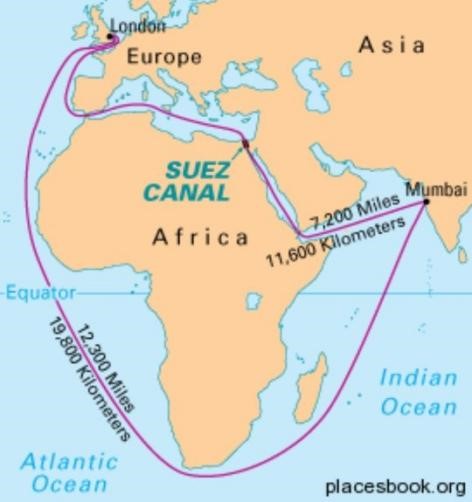

The Suez Canal (Including Strait of Gubal) provides the shortest route between the Atlantic and Indian oceans (saves 7000 Km of extra travel) (See Figure 18). The 120 mile pass goes between Israel and Egypt and passes from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. 100 boats travel the canal daily and 3.9 million oil barrels traveled daily. Thus Around 8% of global sea-borne trade takes place through it. Despite the projects of Canal’s extension, it’ s waters are still congested, making the usage less safe, extending the time and raising the costs of transshimpents.

Figure 18.The Suez Canal (Including Strait of Gubal)

Source:Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

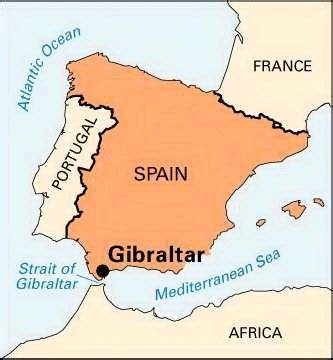

- Connecting the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, the Strait of Gibraltar (including 20 nm either side of Europa Point)is one of the most used shipping routes in the world (See Figure 19). The strait is only seven nautical miles (13 kilometers) across at its narrowest and 23.7 nautical miles (44 kilometers) at its widest. Approximately 300 ships cross it every day, about one ship every five minutes, which causes a high amplitude internal wave, upwelling of nutrient-rich water and affecting bio-life, not mentioning the noise pollution and heavy maritine traffic.

Figure 19. The Strait of Gibraltar

Source:Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

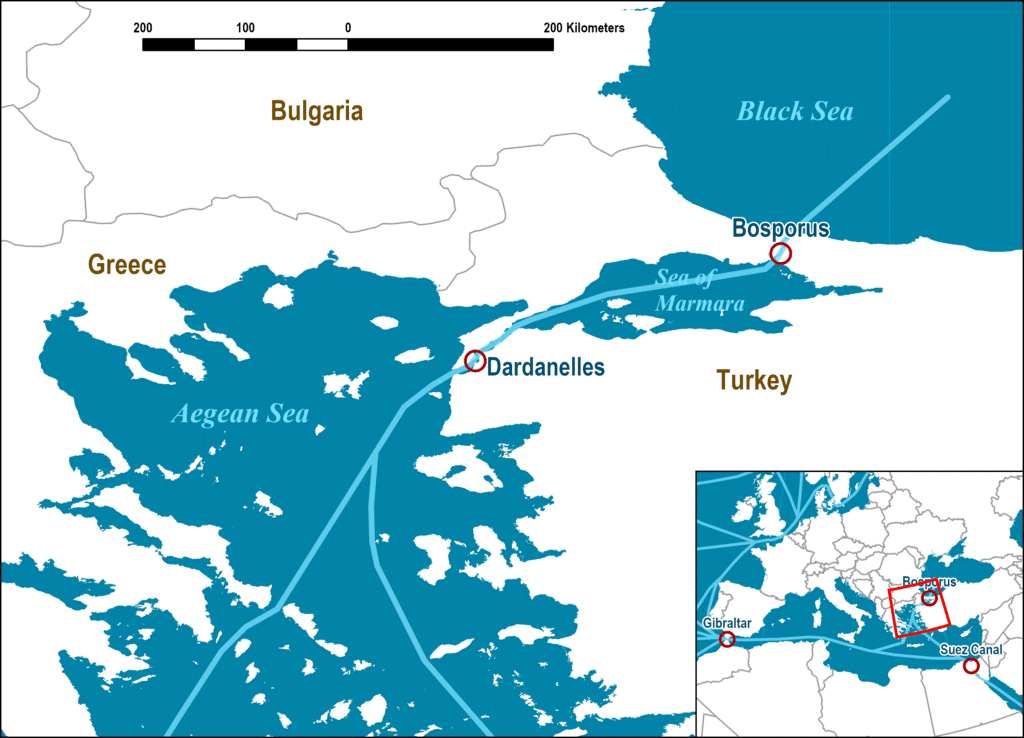

- The Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits separate the Sea of Marmara from the Aegean and Black Seas (See Figure 20). Both straights are on the Europe-Asia boundary and lie within Turkey. The Bosporus is located on the northern edge of the Maramara and southwestern edge of the Black sea. Turkish Straits provide the only access between the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea. The Dardanelles, on the southern tip of the Marmara and northeastern coast of the Aegaen sea (which is connected to the Medeterranean) is wider than its northern counterpart. More than 40,000 vessels are passing through these waters per year, transporting almost 650 million tons of cargo. Located in the area of the conflict of the powers interests, this zone has been always considered vulnerable in terms of safety, not mentioning significant damaging of local maritine biolife.

Figure 20. The Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits

Source: Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

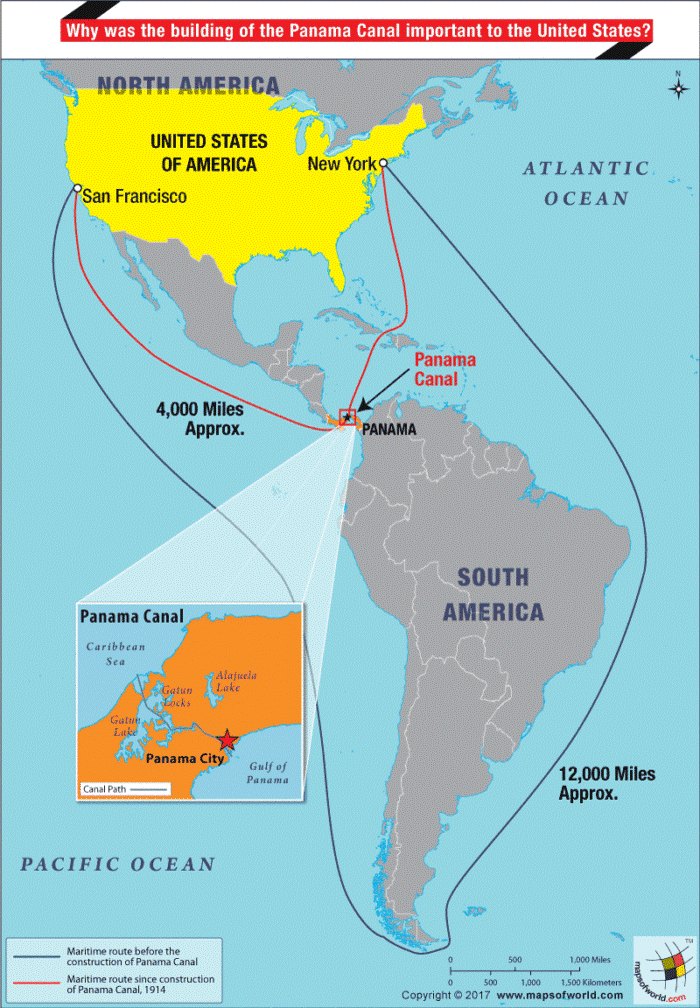

- The Panama Canal is the main crossing point between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean (vessels no longer have to navigate all across the Southern Cone in order to cross between oceans) (See Figure 21), making it one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. It currently allows ships carrying 14,000 TEUs or less to pass. It is estimated that more than 14,000 ships pass through the canal each year. Despite the numerous projects to widen to double the capacity by adding a new lane of traffic, the waters of the Canal are still dangerously congested, influencing not only the cost and time of transshipment, but also damaging bio-systems.

Figure 21. The Panama Canal

Source : Dept. Of Global Studies and Geography, Hofstra University, 2018

Thus, it can be traced that the current sea arteries of warm waters are not just seriously congested (See Figure 22), but also dangerous not only for the ecology and because of security reasons (robbery, piracy etc) (See Figure 23), but also for the stable development of trade and economy. The consequences of these dangers may be fatal in few years (See Figure 24), unless the measurements of improving the maritime transshipment infrastucture are not taken.

Figure 22. Maritime transshiping lines per day

Source :UCL Energy Institute, 2018

Figure 23. Volume of crude oil and petroleum products transported through world chokepoints (2018)

Source : US Energy Information Administration

Figure 24. IMO projections of CO2 emissions from international maritime transport

Source : IEA 2018, IMO 2016, IMO 2019

Global warming is causing vast perennial ice sheets to melt, resulting not only in an environmental threat but also in the opening of economic opportunities.

Today, taking into account the melting of ice in the Arctic ocean, we can talk about the emergence of another alternative to the main transcontinental routes that runs through the Eurasia (green land shipping line), air (white shipping line) and the warm southern waters of Eurasia and further to Africa via Suez canal (red shipping line).

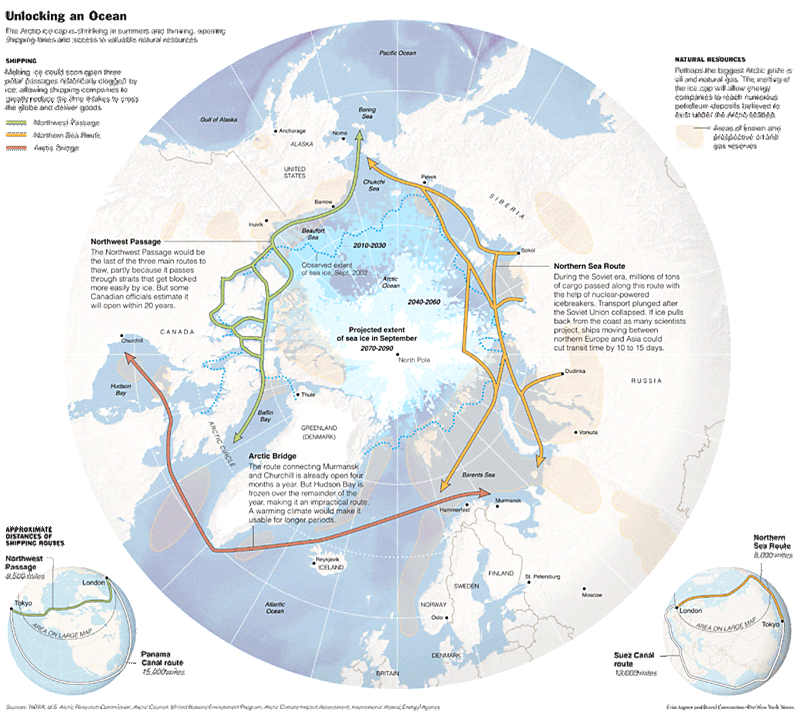

The rapid melting of the north polar icecap, opens the prospects of shortened transport waterways in the ice-free areas. There are basically three possible routes, each of significance:

- the Northwest Passage, connecting the American Continent and Far East Asia;

- the Northern Sea Route, offering a shorter way from Europe to Asia along the Russian Arctic coastline; and

- the Arctic Bridge, connecting Canada and Russia (See Figure 25).

Geographically the position of the North waterways is very beneficial. The Northwest Passage connects the Atlantic and Pacific along the northern coast of North America through the Arctic waters from the Davis straits and Baffin Bay all the way to the Bering Sea shortens the distance between Far East Asia and the American East coast (via Panama) by approximately 7,000 kilometers.

The North East Passage, which connects the Atlantic coast of Western and Northern Europe with the Pacific coast of Northeast Asia via the Russian Arctic coastline, is cutting the distance between the edges of two continents,making it shorter by about 40% in comparison to the traditional, warm seas transport routes via the Suez or Panama Canal.

The Arctic Bridge is a seasonal route which shortens the connection between the North American and European continents via the Arctic Ocean. Observation shows that the transshipment route between the North Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean straight over the Central Arctic Ocean (the so-called Arctic Bridge) might be in reach earlier than expected due to climate change. In this case Iceland’s strategic position will change dramatically and could turn the island into an economic hub – a power base for transportation-related services, bringing along a whole new range of economic activities to the Europe.

Figure 25. Northern shipping. Major transport routes through the Arctic

Source : Centre Port Canada, 2008.

Thus, in terms of logistics, the cold waters shipping line (blue – Northern sea or Arctic passage) will allow to deliver cargo to Europe by sea faster than the 48 days (that it takes on average) to travel from the Northern ports of the Far East to Rotterdam via the Suez Canal, considering that the passage of a cargo ship from Shanghai to Hamburg along the North sea route is 2.8 thousand miles shorter than the route through Suez canal. (e.g. in 2019 the Russian Arctic gas tanker “Christophe de Margerie” reached South Korea from Norway without an icebreaker escort in only 15 days) (See Figure 8).

Another advantage, which play into the hands of the blue transshipment routes is the decrease of using of harmful to the environment material – cement. Building new land infrastructure (especially roads) requires cement, a material that contributes more than 6 per cent of global carbon emissions. Shifting the transportation mode to the sea, therefore, will reduce the amount of roads constructions on the land.

In addition to the time criterion, cold water shipping line is beneficial in terms of capability. It is usually characterized as the shortest sea route between Europe and Asia, the safest (e.g. the problem of Somali pirates) and has no restrictions on the size of the ship, unlike the route through the Suez canal. Thus, the Arctic route will allow to deliver cargo to Europe faster by sea, reducing the route by 20 – 30%, and hence being more environment friendly (by using less fuel and decreasing CO2 emission) and saving human resources. Nevertheless, the capitalizing on that opportunity requires much work in terms of improved navigation procedure and installation of safety-related infrastructure.

But the shortening of the transshipment routes and hence slight decreasing of CO2 emissions will not solve the problem completely. The global environmental issue of CO2 consumption should be treated starting from the main root of the problem and in regards with it Arctic may play the key role.

The projects launched in the Arctic (e.g. project Yamal LNG) meets the goal of reducing the share of coal in total energy consumption in the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters below 58% by the end of 2020, as this project allows to diversify countries' energy sources, contributing to its withdrawal from coal use. This, in turn, reduces CO2 emissions within the country and may contribute to the implementation of the same scheme in the framework of the building of the transshipment routes.

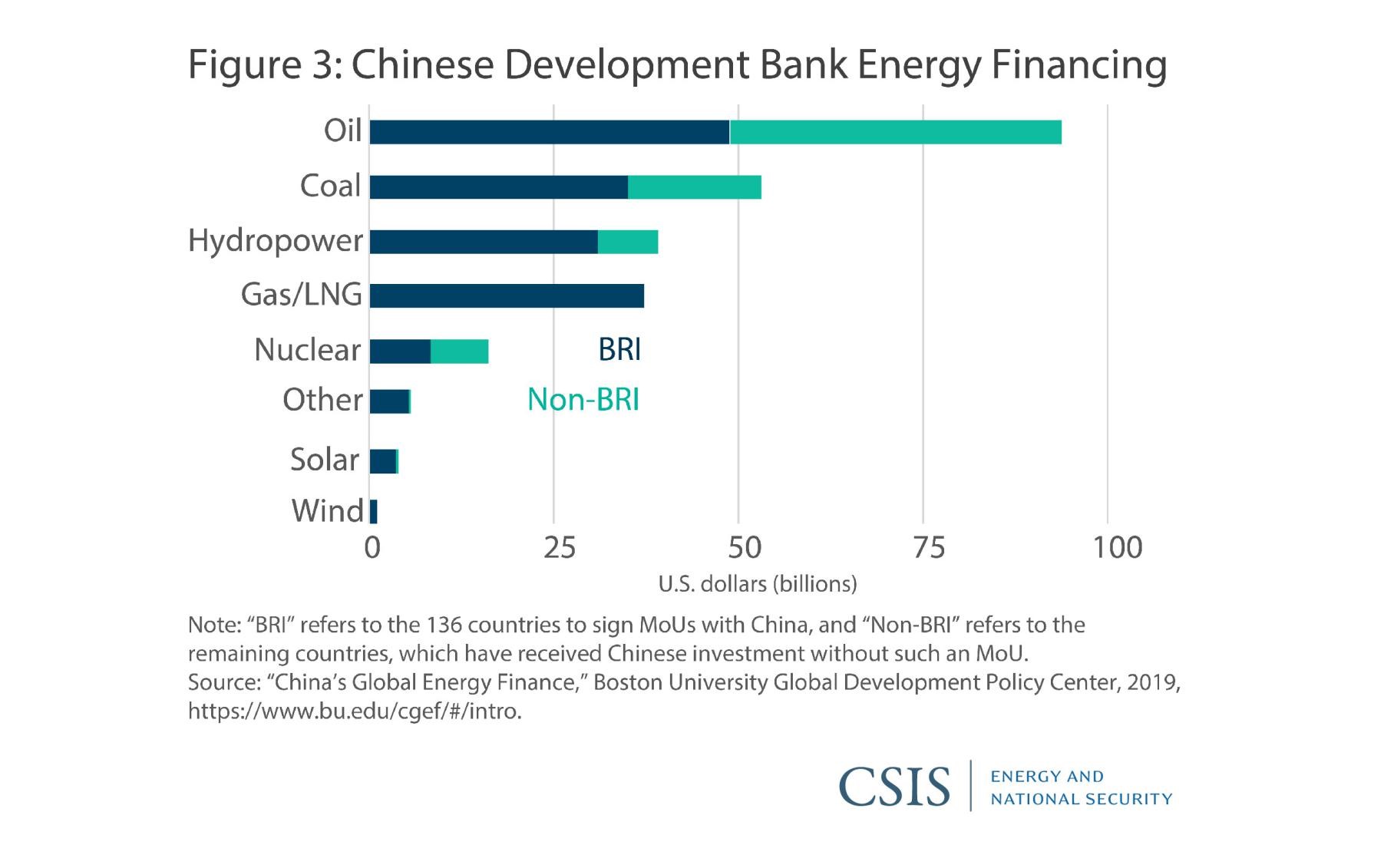

The goal to reduce a dependence on coal and fossil fuels requires a huge surge in the use of natural gas, and the adoption of renewable energy. Which is resulting in not only infrastructure constrictions, but also the development of the projects connected with energy (See Figure 26). One of the key factors driving the implementation of this projects is that, unlike traditional fossil fuels, renewable energy sources are widely available around the world. Whether it is solar or wind power, tidal energy or hydroelectric plants, most countries have the potential to develop some clean energy.

Figure 26. Investments into the Renewable energy projects

Source : Boston University Global Development Policy Center, 2019.

The region covered by new transshipment routes (esp. South – Eastern Europe, Eurasia and South – Eastern Asia covered by Eurasian transshipment lines) has significant potential to be powered by solar energy. Thus it is estimated that less than 4 percent of the maximum solar potential of the region could meet the countries' electricity demand for 2030 which gives the world a possible solution to reduce the countries' need for fossil fuels as they develop.

Only in Europe, due to the implementation of renewable energy projects (e.g. Francisco Pizarro plant in Spain, Nikopol Solar Power plant in Ukraine, Cestas Solar Farm of Bordeaux in France, etc.) the solar capacity increased by 36% to 8 GW in 2018. By 2020, several member states in the European Union pushed to meet their 2020 renewable energy targets.

Along with solar projects, wind onshore wind farms projects (e.g. southeast region of Ukraine, the Fantanele – Cogealac Wind park in Romania, etc.) are also destined to meet increased national energy needs in the wake of phasing out fossil fuel power plants. Thus, the renewable energy potential and cooperation opportunities is a chance for the countries to leapfrog from their carbon-intensive trajectories to low-carbon futures.

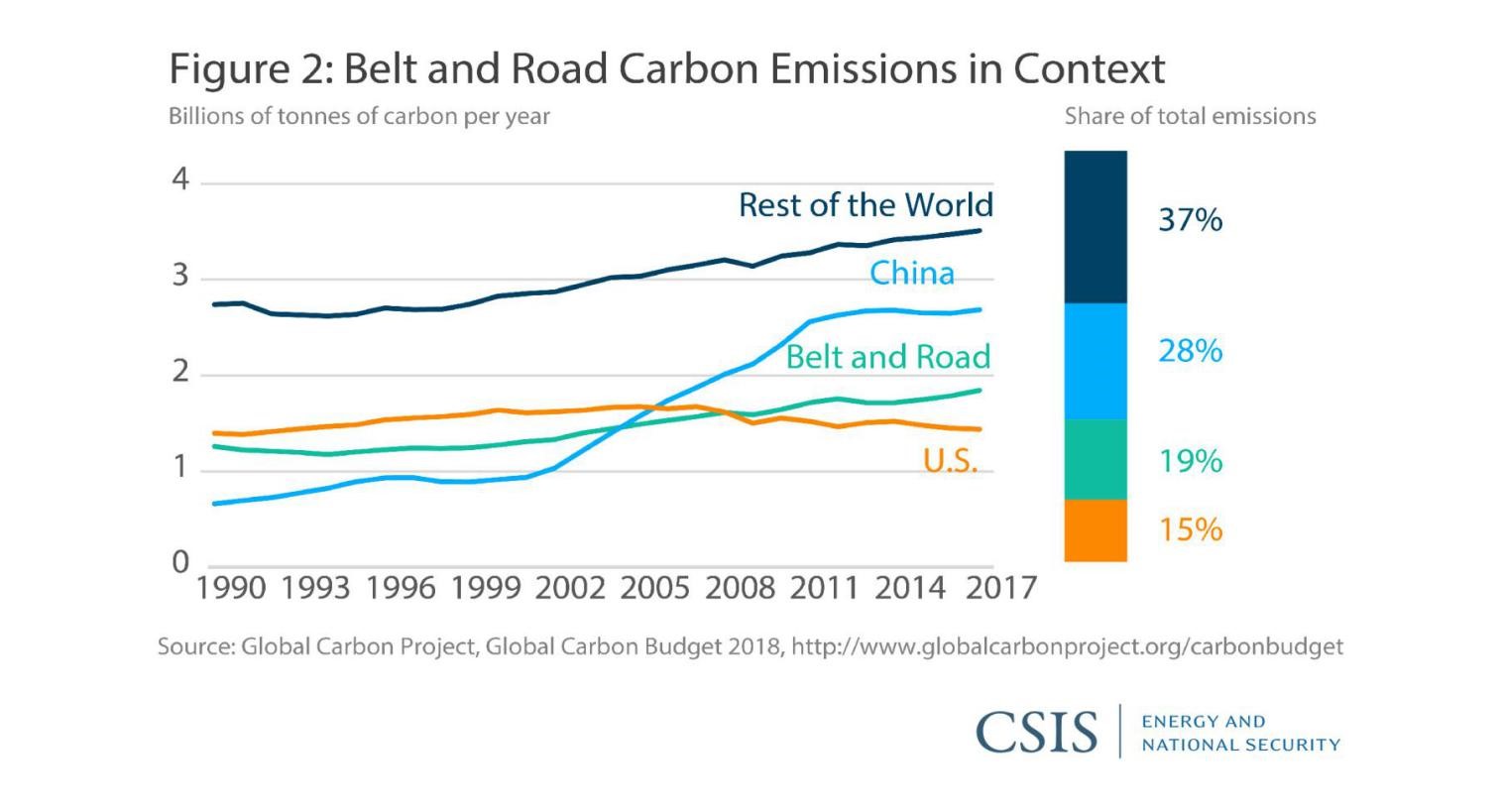

Today countries of Eurasia, not including China, account for about 18% of global GDP and 26% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Current transshipment lines going through these countries are estimated to increase carbon dioxide emissions by at least 0,3% worldwide – but by 7% or more in some countries as production expands in sectors with higher emissions, unless the measures to decarbonize the initiatives are taking. The window for action is narrow: investment decisions made in the coming few years will determine the carbon intensity of critical infrastructure and major real-estate assets that will operate for decades. Thus, by linking policy, finance, and the international community’s expertise and technological resources, it is possible to lay the groundwork for low-carbon development in the countries’ economies. In order to ensure that development in the transshipment lines does not undermine the global climate agenda, meaningful steps must be taken to reduce substantially the carbon footprint of new investments in these economies.

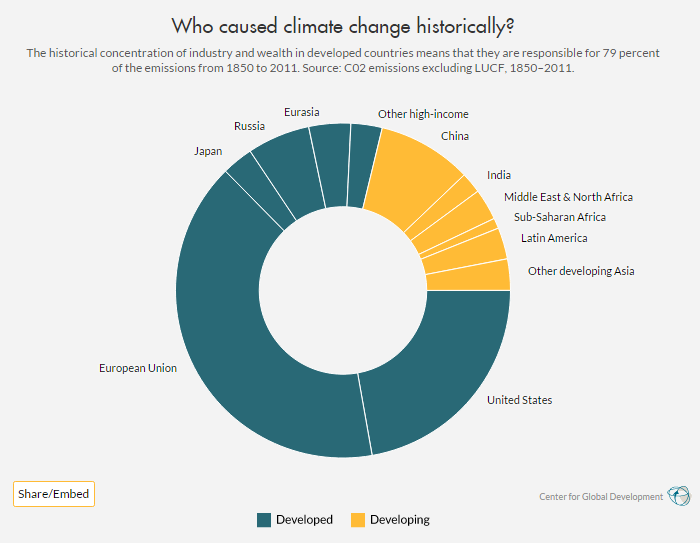

Analyzing this issue it is worth mentioning that the carbon dioxide emissions in developed countries have been in decline for over a decade, and are at approximately the same level right now they were at 25 years ago, while the developing countries are experiencing an explosion in the growth of carbon dioxide emissions (See Figure 27). This is explained by the fact, that developed countries achieved their development on the back of coal, which is now being phased out (See Figure 28). On the other hand, developing countries are currently developing by using coal, and that is driving up their carbon emissions (See Figure 29). It is also explaining the fact that developing countries are not willing to follow stated “greening” goals, since it will require higher financial costs and longer process of the projects implementation.

Figure 27. Carbon Emissions in Context

Source : Global Carbon Project, Global Carbon Budget 2018.

Figure 28. Historical conception. CO2 emissions 1850–2011

Source : CO2 emissions excluding LUCF, Center of Global Development, 2012.

Thus, the only way to actually implement the “greening” of the current and future transport infrastructure is “add teeth to environmental rhetoric” in such project as Tuzla coal-fired power station in Bosnia and Herzegovina, or a coal-fired power station of Kostolac B3 in Serbia. It is not enough to promote best practices without altering problematic behavior, nor is it enough to simply provide spaces for discussion without empowering members to act.

As long as projects’ investors only adhere to host country regulations, the most direct way of improving their practices would of course be for those countries to facilitate improved environmental standards because at some point, countries have to be responsible for their decisions.

Figure 29. Carbon Dioxide Emissions by developed and developing countries 1965–2019

Source : BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2020.

For now it can be seen that there are two possibilities for developing transport systems and economies in accordance with green standards :

- Transcontinental railroad system (which requires huge amount of investments) (See Figure 7);

- Optimization of the cheapest mode of transportation (maritime warm waters transhipment lines) (See Figure 8).

But while thinking on the best ways of the decarbonizing of transport connections between the most-producing countries of G-7 (Atlantic states and other European countries) with other advanced OECD economies, all the existing risks (such as “convenience”, roads “safety”(piracy, oil spills), water congestion levels and maritime traffic) should be taken into account. As itwas mentioned above,warm waters transshipment lines(See Figure 11) currently present certain dangers, being high congested and unsafe (both for trade security and environment), and hence rather vulnerable. Due to this fact, it is crucial to consider other alternatives of connecting the biggest countries-producers (Far East) and countries-consumers (West Europe).

The development of the cold waters (i.e. Arctic passage or blue line shipping line) route (See Figure 8) may serve as an alternative which can be beneficially both in “convenience” and environmental issues because it is time-saving transportation of goods from Far East to European countries, as well as the possibility of improving the energy problem in the world’s largest emitters, on the solution of which, in turn, depends the regulation of the global environmental issue. As professor Anis H. Bajrektarevic elaborated in his seminal work on Polar affairs, comparing contrasts of Arctic and Antarctic trasshipment roads, three possible passages may be considered (See Figure 25). Nevertheless, though there is high potential to slash international shipping distances by opening shorter routes in the north, the high risks on these alternative routes are still keeping most traffic running over the classic transport routes like the Suez and Panama Canals.

While summing up the data on the logistics, it may be seen, that Blue shipping line along with Green one (See Figure 8) will dramatically reduce the time between the most-producing countries of G-7 and advanced OECD markets. But to reach consensus in timing, price and environmentally friendly standards the growing push to decarbonize economies, implement the green construction methods should be done. Unfortunately this approach may take decades to be adopted, which our planet may not have. And understanding of this fact should underlie the development to all the countries of the Globe without exceptions.

Conflicts will of course arise between the green agenda and concerns about costs to consumers. These conflicts will be most apparent in countries where pressures from fast rising populations and urbanization are the highest. The key question is whether governments prioritize short-term cost savings over longer-term benefits that come with sustainable development.

To address this issue, it would be useful if entities such as the International Institute for Middle-East and Balkan Stuies - IFIMES (of the Specialized status with the United Nations system) could conduct various types of awareness campaigns, P2P diplomacy and other operational events and high-impact gatherings – all similar to the Vienna Process,which this Institute started together with its partners to promote sustainable policy proposals for attainable future. Based on the IFIMES advocacy and fine diplomatic work, the MDBs, international financial institutions and developmental agencies should provide technical assistance and incentivize wherever possible. While the new synergies among the international FORAs of different scope and mandate can help with the latter, the greenification will only be successful, if translated into concrete actions, such as the adoption of the “best national standard, including monitoring of compliance” as well as widening and deepening of the additional enforcement and incentivization mechanisms.

Scope and speed of action is crucial. No more time for this planet to waste. Action will only come when the political will is truly and fully behind it. Therefore, the International Institute IFIMES addresses with this study mainly the national subnational and supranational decides-making levels. It is the utmost wish of the author that this supervised mini study is considered as a policy orientation, tentative road-map for the urgent global greenification.

* * * * * * * *

The increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases and harmful emissions into the atmosphere is getting worse every year. Analyzing the possible ways to solve the fundamental problem, the author emphasizes the importance of the largest land mass of the globe - Eurasia and transport logistics through it. The author analyzes three possible ways of developing Eurasian transshipment lines in accordance with green standards. The main problems and opportunities of railway roads, Southern warm congested waters are considered. Special attention is paid to the development of Northern waters transshipment lines between the most-producing countries of G-7 and advanced OECD markets

Keywords: Decarbonization; Transport; Logistics, Greening; Railway, Arctic transhipment lines

About the author:

Dr Maria Smotrytskais a senior research sinologist, specialized in the investment policy of China; BRI-related initiatives; Sino - European ties, etc. She is distinguished member of the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists. She has PhD in International politics, Central China Normal University (Wuhan, Hubei province, PR China).She is currently a content provider for the media platform Modern Diplomacy and the Institute’s research fellow.

Ljubljana/Shanghai, 8 February 2021

Footnotes:

[1] IFIMES – International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies, based in Ljubljana, Slovenia, has Special Consultative status at ECOSOC/UN, New York, since 2018.