International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES)[1] from Ljubljana, Slovenia, regularly analyses developments in the Middle East, Balkansand also around the world. Dr. Antonia Colibasanu is Geopolitical Futures’ Chief Operating Officer. In her comprehensive analysis entitled “European Reconstruction: A Project Born of Uncertainty” she is analysing the Franco-German proposal for the European Union’s economic recovery after the coronavirus crisis and the impact it will have on the future of EU.

● Dr. Antonia Colibasanu

The Franco-German proposal for a recovery fund sends a message of political realism.

France and Germany on May 18 proposed a plan for the European Union’s economic recovery after the coronavirus crisis. The proposal calls for the creation of a common fund filled with money the European Commission would borrow from capital markets and channel to member states to fund their recoveries.

It marks the first time Germany has given in to the idea of borrowing money together with other EU member states. It comes after the German Constitutional Court rejected the potential issuance of “coronabonds,” joint debt for which all EU countries would have been equally liable. The current proposal calls for joint debt, but it would be guaranteed by the EU budget and not by all EU countries individually.

On May 23, the so-called Frugal Four – Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden – sent a joint letter to all EU capitals laying out their position on the Franco-German proposal. While the media touts it as a counterproposal, the frugals’ scheme is similar to what Paris and Berlin presented. They want a common fund from which aid money would go to economic sectors particularly affected by the crisis. Unlike the Franco-German plan, the money would be repayable – distributed as cheap, but not free, loans as opposed to transfers. The Frugal Four do not want to see debt mutualized, but far from killing the Franco-German proposal, their plan marks the beginning of the negotiations on the details. With their paper, the frugals, the most conservative and cautious group of countries in the EU, want to show their electorates that they are proceeding with care, while pointing to the risks of EU fragmentation, single market dysfunction and extraordinary economic hardship ahead.

There are three elements in the Franco-German proposal that need to be considered, as they point to the way the two countries envision the EU’s future. First, it is worth nothing that the phrase “European sovereignty” is repeated several times. Second, the project is linked to the Multiannual Financial Framework, the long-term budget of the union, meant to finance its strategic development. Finally, no matter what the member states decide on the details, it is the European Commission that is supposed to announce them, which highlights an interesting, synchronous choreography between Paris, Berlin and Brussels. Some issues are probably already agreed, while others will be discussed behind closed doors, but Brussels needs to appear to be in charge of the process, even if in reality France and Germany will orchestrate things. Negotiations between the member states will likely concern those elements referring to the political (and possibly legal) framework for the proposed economic recovery fund.

Though we don’t know how the money will be distributed or whether it will come in the form of grants or loans, we do know that it will be funded by European Commission borrowing and that it will be part of the EU’s seven-year budget, and thus earmarked for investment. Starting from the assumption that Europe will face an economic recession after the crisis, the Franco-German short-term plan aims at measures relating to “resilience, convergence and preservation of European competitiveness” so that recession doesn’t turn into depression. In other words, from a political point of view, the text of the agreement wishes to convey that France and Germany are willing to do anything to keep the EU together, whatever the economic consequences of the crisis.

Since it is part of the Multiannual Financial Framework, the recovery fund links the member states through the EU’s critical infrastructure, which takes on a new meaning in the wake of the pandemic. Specifically, the areas of European sovereignty, as they appear in the text, are public health, digitalization and new renewable energy technologies – all critical infrastructures that have traditionally belonged to the member states.

Through their plan, Berlin and Paris are looking to establish a common European economic and industrial base, which means putting more power in the hands of Brussels. The areas chosen suggest that the European Union wishes to be more independent from the outside world, focusing on building itself internally. The shock to global supply chains has shown Europe’s vulnerability to pharmaceutical imports from China. European dependence on Russian energy imports has long been problematic, and while developing green energy is costly and complicated, France and Germany regard this crisis as an opportunity to take on that challenge. And the crisis has shown Europeans how important a flexible and secure digital infrastructure is for allowing work to continue under social distancing.

It is unclear how these three important sectors can be built up into a cohesive infrastructure that covers the entire European Union. The Franco-German plan offers no details on how existing industrial bases will be connected with new facilities, nor does it seem to consider differences among member states. But the text suggests that the funding will only be given if it is linked to the idea of common, sovereign European investments that are controlled by the European Commission.

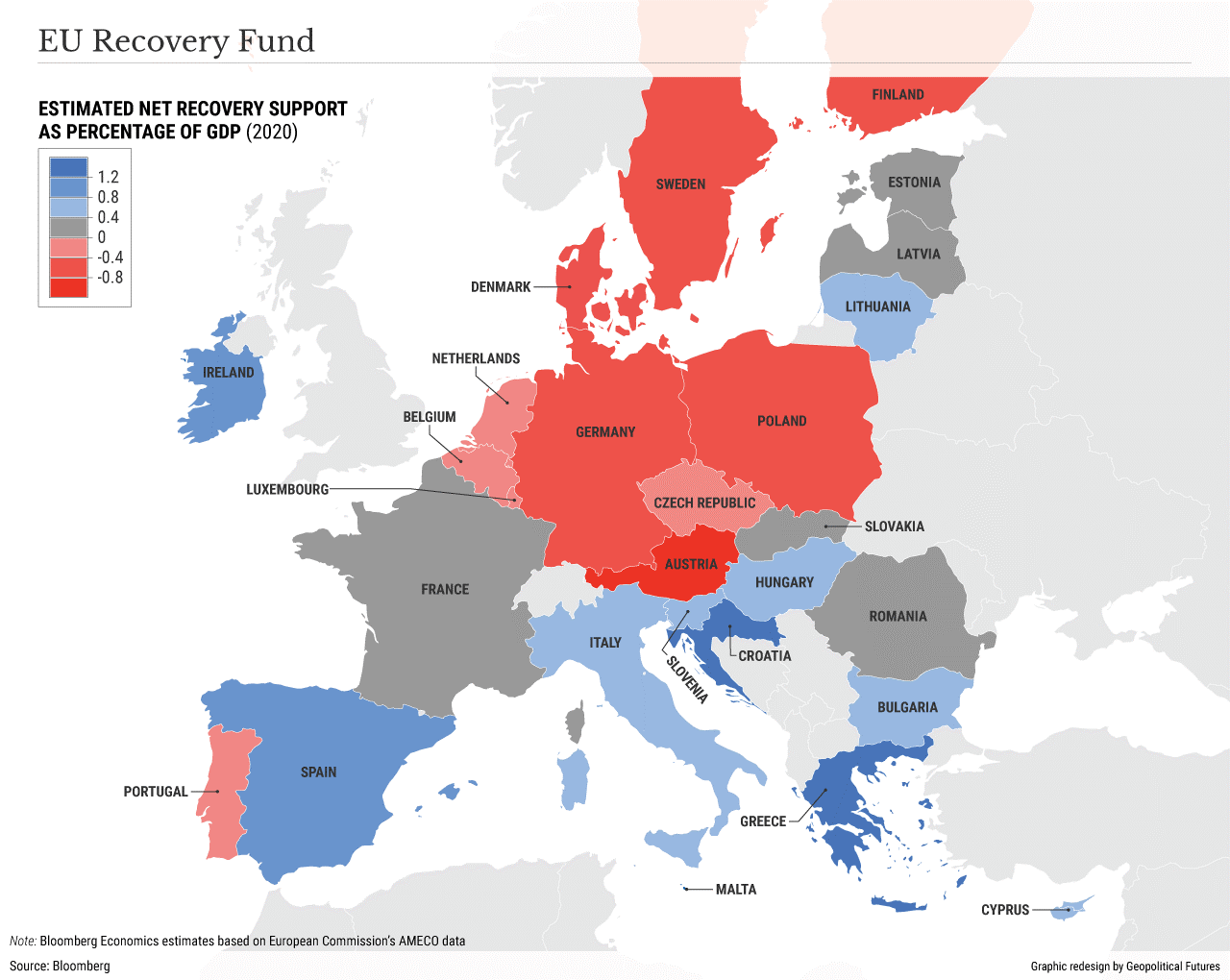

The proposal also says that the countries most affected by the coronavirus crisis will be given priority. It adds, however, that there will be conditions linked to “sound economic reforms” and an “ambitious agenda” for their implementation. It therefore appears that Germany and France want a system whereby grants or loans are linked to economic performance, at a structural level, even though all economic sectors are seen primarily and intrinsically as European rather than national.

This focus on European interconnectedness and sovereignty points to a new step in European construction. In order to achieve these common objectives at a structural level, the EU needs more common, or at least coordinated, fiscal policy – coordinated monetary policies are not enough on their own. And in order for this to be possible, the EU must truly coordinate at the political level.

There was little to unite the member states politically. But during exceptional times, things can change. Germany is willing to let the European Commission borrow money, collectively with the other member states. It is willing to take this risk and have Italy and Spain spend most of the funds during the next three to five years. It needs the EU common market to survive, and it needs the eurozone to hold together. And, along with France, it is willing to formally take the lead.

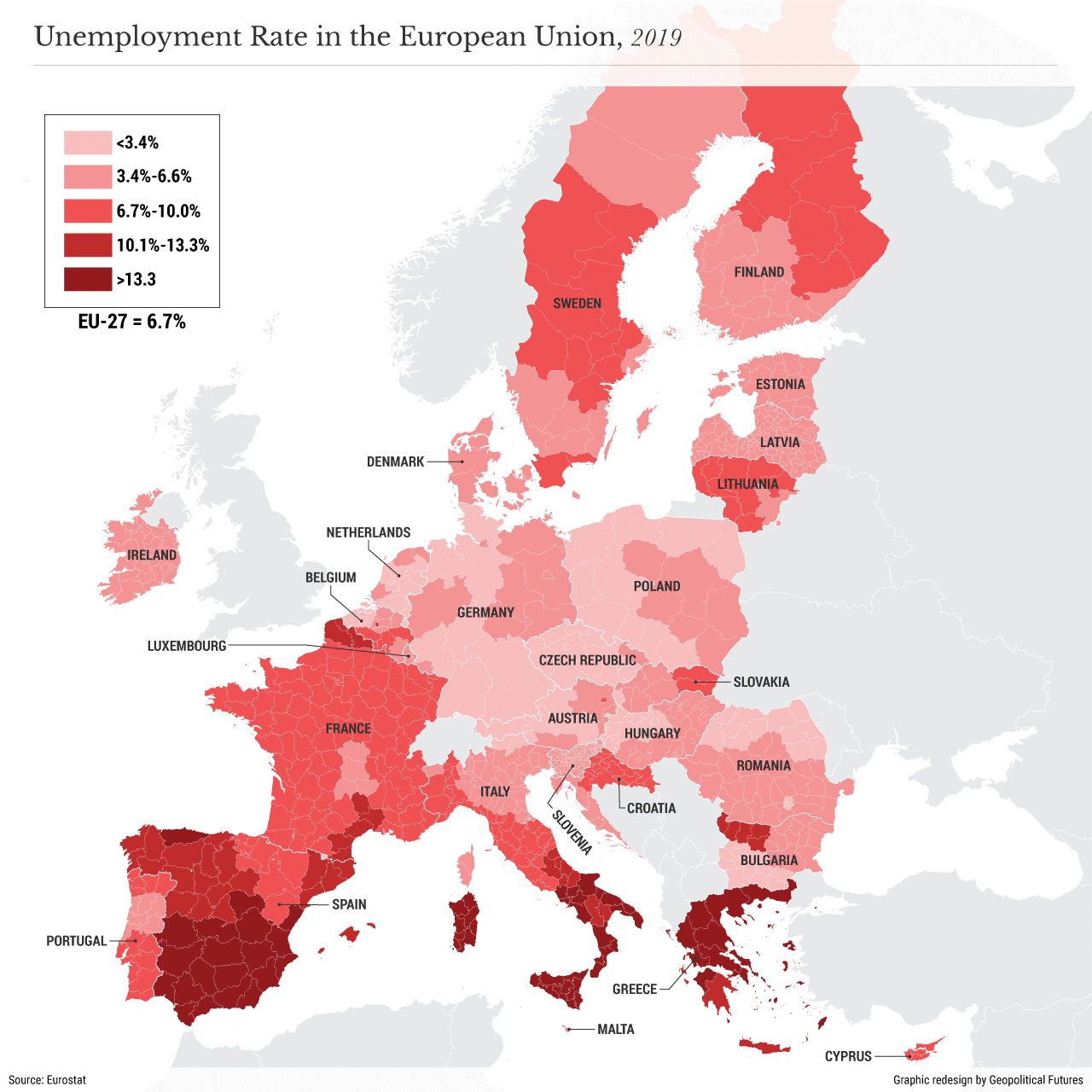

The recovery fund proposal is being discussed at the same time as talks on the EU’s long-term budget and strategy. Initial data released by the German government on May 25 confirms that Germany entered technical recession in the first quarter of 2020 due to the coronavirus crisis. In the eurozone, annual inflation keeps decreasing, which points to the risk of unemployment surging once the crisis is over. There is not enough data to know how badly the economy will be hit – all we know is that it will be hit hard.

Two months ago, the Europeans were preoccupied with discussions about funding the Green Deal for the next seven years. Now, Europe will certainly face new socio-economic problems, caused by unemployment and systemic failures, which will likely increase political instability. This is why politicians feel that they need to act urgently, to at least show that they did something.

Germany can’t afford to look like it isn’t supporting the eurozone anymore – even if the German electorate won’t endorse the same policies it did during the 2008 financial crisis, especially in light of its own socio-economic problems. France needed to rebuild its economy even before the coronavirus pandemic; it now needs to do it much more quickly.

By integrating the Franco-German proposal into the Multiannual Financial Framework, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel have made the funding conditional, considering the member states’ contributions to the union’s budget and resetting strategic priorities at the EU level. The funding doesn’t address specific problems of specific countries; it covers EU problems only. So, it’s unclear whether the EU will grant exceptions to the financial contribution rule – which will tell us how the loans contracted by the European Commission will be repaid by member states, and how it will be given to states, i.e., by grant or loan.

The areas that will receive funding are not so different from those laid out by the commission in its proposed budget before the crisis. In addition to digitalization and green energy, which were under discussion before the pandemic, the proposal suggests funds will be allocated for health care systems and for the pharmaceutical industry. Southern and Eastern European states aren’t major pharmaceutical producers, of course. Germany and France are. The new budget will benefit the western states more than ever before.

In addition to these east-west disparities, Brussels will have to manage the north-south divide. While the northern European member states are most reluctant to accept plans involving high spending for the common good and are trying to limit grant funding, the southern European states have already announced their support for the Franco-German initiative and wish to further discuss the details, even if these member states ultimately don’t have many assets in the pharma or the green energy sectors. Here, reviving economies mostly concerns sectors such as tourism.

More notable is the muted response from member states outside the eurozone. Poland has expressed its reservations toward the plan, while the others wait to hear more about the implementation rules. It is likely that negotiations will involve only eurozone members for now. In other words, while greater fiscal unity is under discussion in the EU, the question of how non-eurozone countries will be funded and integrated remains unanswered. This only reinforces the differences between east and west in the EU.

The Franco-German proposal is now under discussion at the EU level, and we will hear more about how and what will be negotiated in the coming days. Until then, we can at least say its very existence illustrates important geopolitical realities, not the least of which is that, because of their shared reliance on the single market, Germany and France agreed to launch this political catalyst. It shows that they, along with the Frugal Four, are aware of the EU’s fragility in these unprecedented times.

The proposal sends a message of political realism. As the United States and China contend with major structural problems – and with each other – neither France, nor Germany, nor the Frugal Four can cope with the coming recession or depression on their own. In the past, they could more or less compensate for EU market troubles by turning toward the U.S. and Chinese markets. This is no longer available, hence making the EU markets and integrity all the more important. Moreover, they depend on the economic ties between them, which are simply too deep to be undone from one day or even one year to another.

The EU also sees the need to present a stronger, more united front for emerging risks in its immediate neighborhood. Russia’s economic problems could make Moscow more aggressive abroad, Turkey is becoming a new Ottoman Empire and Brexit is still a big unknown. The EU is right to be afraid. The battles in the eurozone are hard enough to win without including more outside powers. Faltering domestic economies would make things only worse for Germany and France. They figure they had better not lose what they currently have.

This is to say nothing of how the pandemic has aggravated existing notions of nationalism. People are going to become increasingly restless as social isolation and distancing policies remain in place, especially as the economic problems from those policies become more apparent. The need to forestall crises will force political leaders to maintain the status quo as best they can, focusing on existing relationships and trumpeting the importance of the European project. They understand their careers and indeed the potential of the EU are at stake. Traditional politics took a beating after the 2008 crisis. Another one could well be the death blow.

This is why the stakes of political negotiations, too, are much higher now that it’s clear that the economic recovery will require more than a purely economic solution. But the economic aspect is still critical. And according to the documents laid out by France and Germany, and reinforced by the Frugal Four, access to funding rests on meeting preconditions. We’ll know soon enough if this is a step forward for shared sovereignty for all or for a select few. The EU core is clearly worried about the bloc’s future. Ironically, the plan can go both ways: It may bring more cohesion for the short term and, under certain conditions, it may get the EU to the next level of integration, making it a political actor. Or, it may lead to deeper fragmentation.

About the author:

Dr. Antonia Colibasanu is Geopolitical Futures’ Chief Operating Officer. She is responsible for overseeing all departments and marketing operations for the company. Dr. Colibasanu joined Geopolitical Futures as a senior analyst in 2016 and frequently speaks on international economics and security topics in Europe. She is also lecturer on international relations at the Romanian National University of Political Studies and Public Administration and associate professor for the Romanian National Defense University Carol I Regional Department of Defense Resources Management Studies. Prior to Geopolitical Futures, Dr. Colibasanu spent more than 10 years with Stratfor in various positions, including as partner for Europe and vice president for international marketing. Prior to joining Stratfor in 2006, Dr. Colibasanu held a variety of roles with the World Trade Center Association in Bucharest. Dr. Colibasanu holds a Doctorate in International Business and Economics from Bucharest’s Academy of Economic Studies, where her thesis focused on country risk analysis and investment decision-making processes within transnational companies. She also holds a Master’s degree in International Project Management. She is an alumna of the International Institute on Politics and Economics at Georgetown University.

Copyright 2020 Geopolitical Futures, LLC. Republished with permission.

Ljubljana/Bucharest, 26 June 2020

Footnotes:

[1] IFIMES - The International Institute for Middle-East and Balkan Studies, based in Ljubljana, Slovenia, has a special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council ECOSOC/UN since 2018.