International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES)[1] from Ljubljana, Slovenia, regularly analyses developments in the Middle East and the Balkans. Dr. Antonia Colibasanu is Geopolitical Futures’ Chief Operating Officer. In her comprehensive analysis entitled “Postponing an Oil Production Catastrophe” she is analysing situation and changes in the energy market in the time of coronavirus pandemic.

● Dr. Antonia Colibasanu

Fresh off helping to broker a global agreement on oil production cuts on April 12, U.S. President Donald Trump has declared American cuts a priority for the country. Texas, however, said it needed more time.

The Railroad Commission of Texas spent April 14 debating whether the state’s oil output should be reduced. The commission regulates Texas’ energy sector, which means it oversees about 40 percent of the United States’ oil and gas production. Like other producers around the world, U.S. shale producers have seen prices crater since late February as the coronavirus crisis set in. And like other producers, the U.S. was hurt by the price war launched in early March after a first attempt at an OPEC+ deal fell through. But pressure on the U.S. has been reduced by this week’s deal, which came about after the scale of the economic damage in Europe and the U.S. persuaded Russia to give way. American producers were also aided by Saudi Arabia’s decision on April 13 to shift more of its supply toward Asia to reduce pressure on the U.S.

Nevertheless, the size of these moves pales in comparison to the challenges ahead. If no adjustment had been made, the point at which production would have become unprofitable would have been weeks away. But with the output cuts announced this week, if current conditions hold and economic activity doesn’t pick up in May, the unprofitable threshold will be crossed in a couple of months. The cuts are clearly not enough to restore the market equilibrium, but they are the best that countries can do right now.

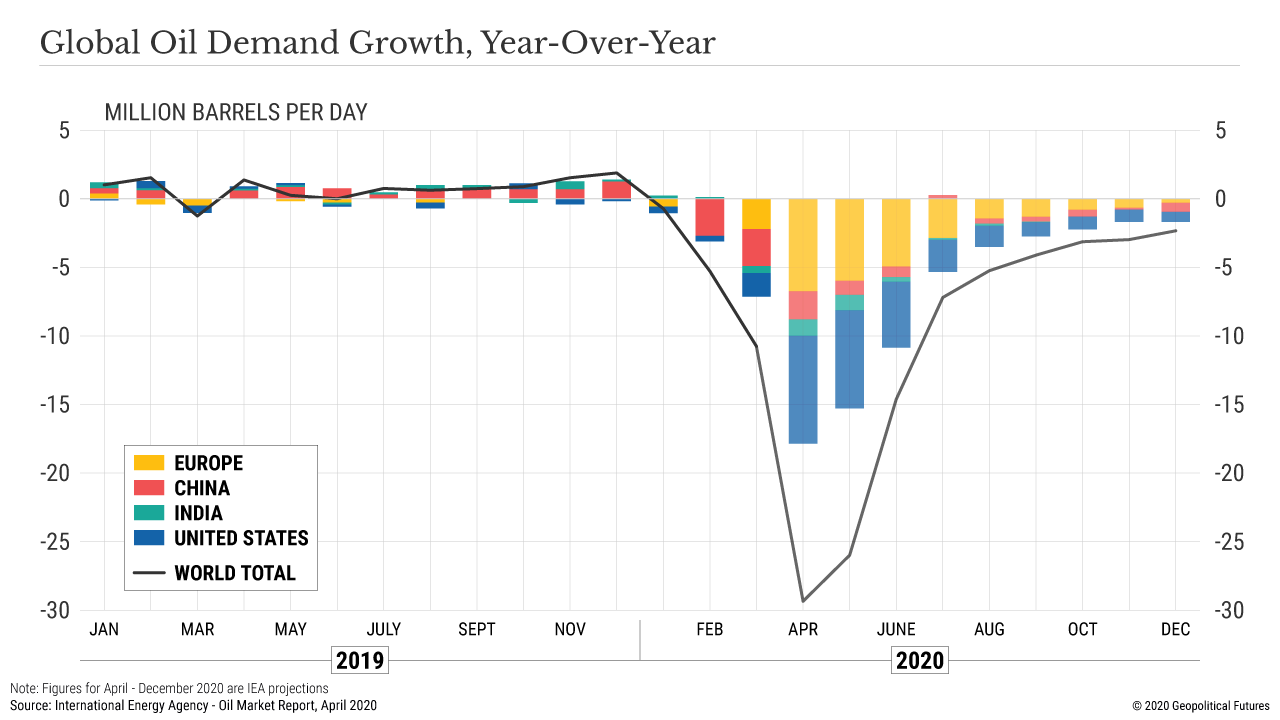

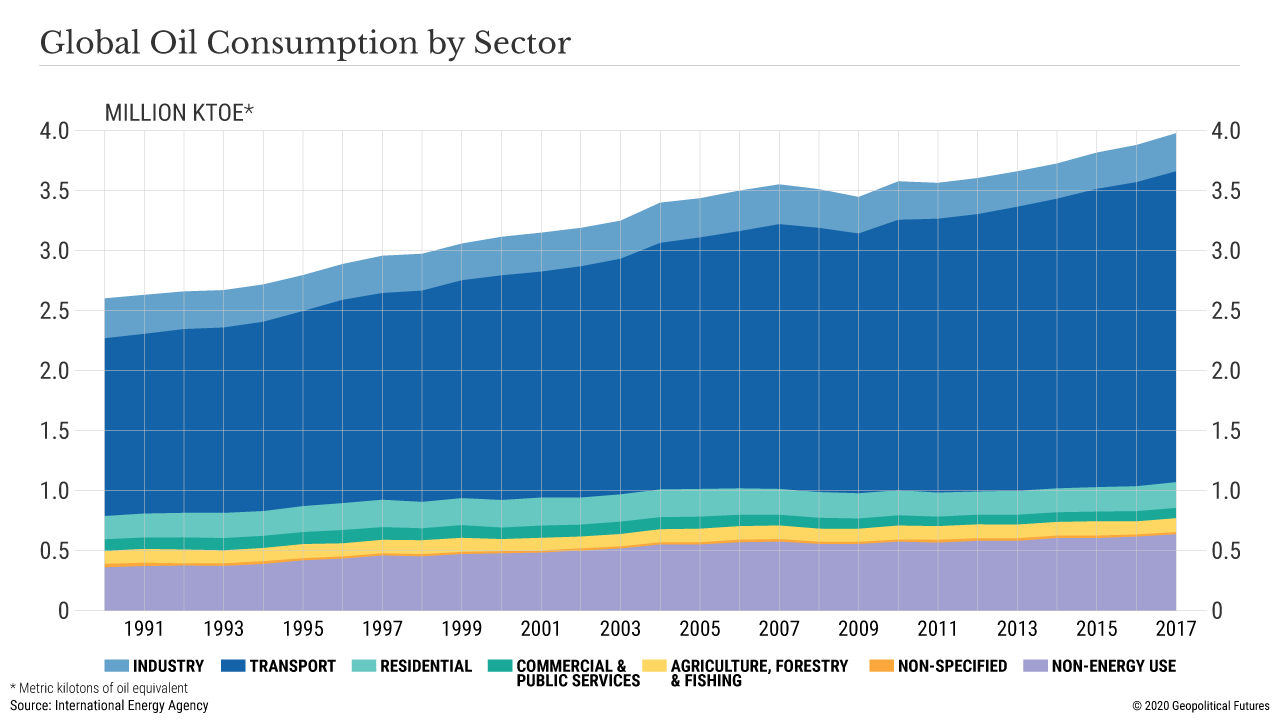

Oil demand is relatively inelastic — the quantity purchased doesn’t change much when the price does. Yet small changes in demand create sudden (and sometimes dramatic) changes in price. According to the International Energy Agency, China’s lockdown caused a decrease in demand in February of 1.8 million bpd compared to February 2019. Global demand as a whole fell by 2.5 million bpd year-over-year (about 35 percent) during the first quarter of 2020. It also anticipates that the coronavirus pandemic will generate a drop in demand that’s similar to (or worse) than 2009 crisis levels — and that prediction assumes, rather optimistically, that demand returns to normal levels during the second half of 2020. This is impossible to know: Global supply chains have broken down as the coronavirus put countries in lockdown. With emergency measures in place all over Europe and the U.S., the key consumers of oil such as airlines and factories have stopped consuming. Social distancing means that people are mostly indoors and businesses are at least partially shut down. If we knew how long this state of affairs was going to last, we could calculate its impact — but we don’t.

In times of less uncertainty, OPEC has often chosen to micromanage the oil market by subtracting small quantities of supply to balance market prices. Countries with the highest levels of production and flexibility, like Saudi Arabia, could use the cartel to manipulate pricing to their advantage. But never before have changes occurred over a timeframe of several months, with no end in sight, and never before have fluctuations in demand been more than a couple of million barrels per day; analysts now discuss a drop in demand of between 15 million and 35 million bpd over the first quarter, with the bulk of it happening during the last three weeks of the quarter, when the U.S. implemented its emergency containment measures.

The OPEC+ deal on April 12 means to reduce oil output by 9.7 million bpd, just short of the 10 million bpd that OPEC members wanted and market analysts expected. This is obviously too little to bring supply in line with demand, considering the demand projections cited above. But it helps delay the onset of the disaster and allows key political players to save face.

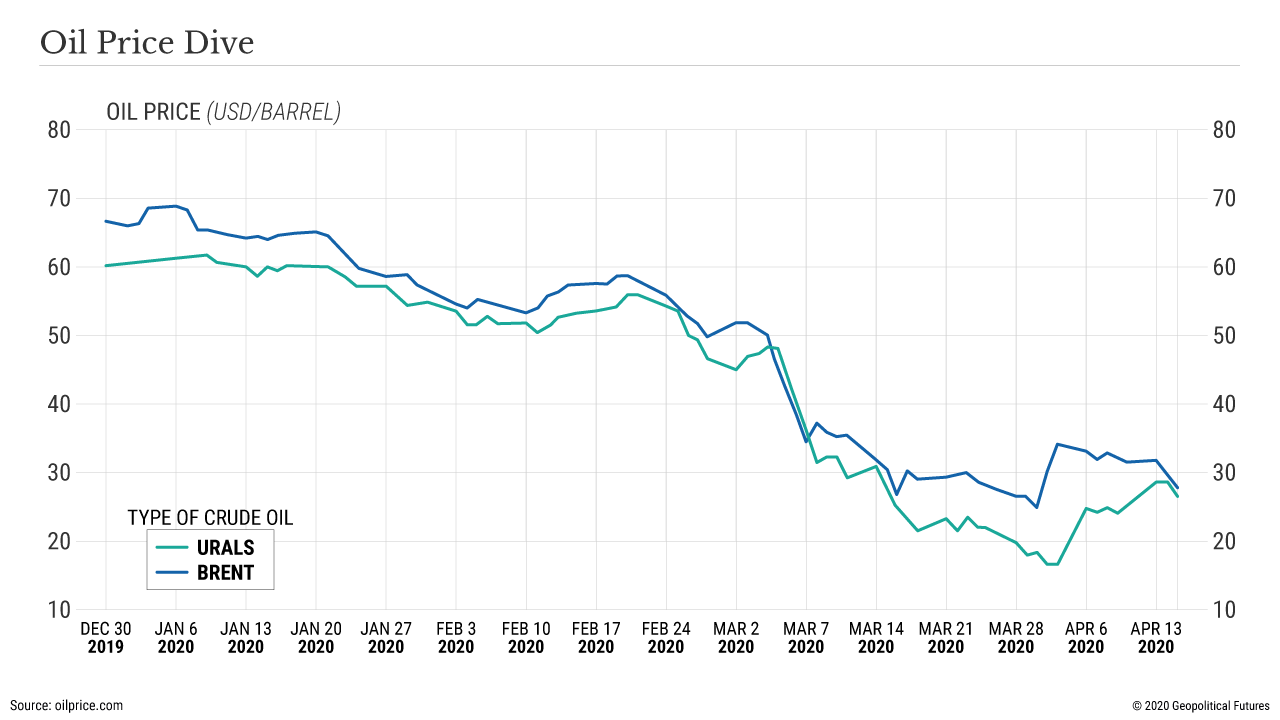

The idea of a supply agreement dates back to February, when a drop in demand of nearly 10 percent — led by China, the world’s largest importer of crude — began to affect market pricing. Saudi Arabia turned to OPEC, expecting OPEC members and affiliates to follow its lead and voluntarily cut production by 1.5 million bpd. Everyone signed on to the idea except Russia. Russia’s budget is balanced at a lower oil price than it is for Saudi Arabia and other OPEC members, enabling Russia to ride out lower prices while maintaining a budget surplus. And considering its sluggish economic growth since 2015, Russia also wanted to bring more oil to market to bring in extra revenue. Moreover, Moscow saw an opportunity to push U.S. competitors out of Europe by driving prices down to levels at which U.S. shale production would be unprofitable.

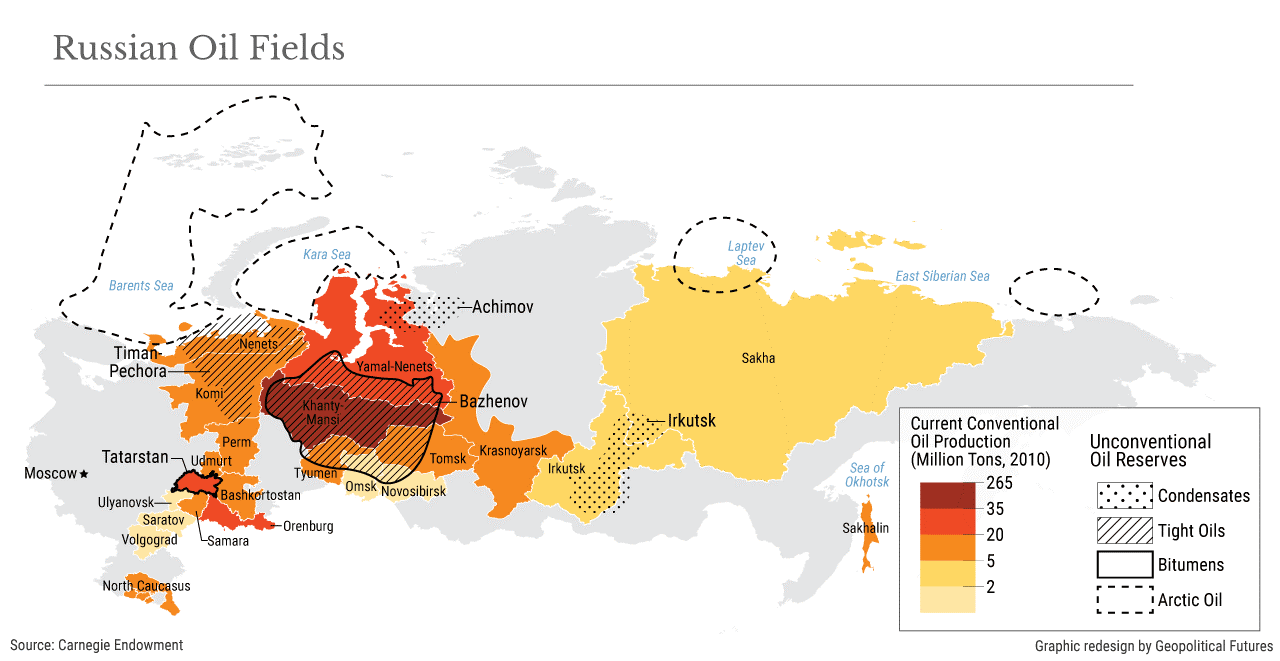

Finally, Russia’s climate and geological conditions make it costly for the country to reduce output. Unlike its competitors, Russia gets most of its output from bitterly cold environments, where costs are higher due to technology needed to keep crude flowing into pipes and to keep gas from freezing. In fact, oil extraction is currently unprofitable in about 33 percent of Russian fields. The quality of Russia’s reserves has been deteriorating for the past decade, and production is on the wane. Therefore, the most Moscow was willing to do in early March to reduce output was what it had always done: to feign cooperation and scale up seasonal maintenance periods to slightly reduce output temporarily.

In response, Riyadh launched a price war. It started bringing its spare production online to see how much oil it could dump on the market and to force Moscow to capitulate. Saudi exports grew by over 1 million bpd in March. The effect of cratering oil prices at the same time that the coronavirus crisis’ economic consequences were becoming clear was enough to drive all oil producers back to the negotiating table — at the urging of Washington.

In late March, things changed rapidly for Russia, too. The coronavirus outbreak in the country was so widespread that it could not be denied. The government imposed emergency measures, including quarantine, in Moscow and other major cities. More important, the virus was hitting Europe hard. Europe is Russia’s most important energy market, and as Europe went into lockdown in the first half of March, Moscow saw its price of oil slip into unprofitability for the first time. Finally, as the scale of the economic downturn became clear, Russian concern about its financial reserves grew. Russia holds about $560 billion dollars’ worth of financial reserves, but most of it is not denominated in U.S. dollars. This means the value of these reserves decreases as the U.S. dollar gets stronger relative to other currencies — which tends to happen during global crises as investors rush to the safety of the dollar. All these factors combined to push Moscow to compromise. The last thing President Vladimir Putin wants is to be blamed for economic mismanagement — if reserves drop in value and Russians have to suffer, it needs to be someone else’s fault and not Moscow’s.

American shale oil companies, like other producers, have been struggling with falling prices since March. U.S. President Donald Trump, facing a re-election campaign and a plunging economy this year, had to respond and therefore made an agreement on production cuts a priority. Apart from the OPEC+ deal, the U.S. got extra help from the Saudis. On April 13, Riyadh announced that it had added $5 to the price per barrel of crude shipped to the United States, while cutting $5 from the price for Asian deliveries. This means the Saudis will stop dumping crude oil on the U.S. market, and therefore many U.S. producers — mostly shale producers — will stay in business a little longer.

Without Saudi oil on the U.S. market, American production doesn’t really need to be cut. The nature of U.S. shale is different from that of more conventional oil fields. Shale isn’t pumped; instead, natural pressure in the rock formation pushes the oil up and into pipes that carry it to loading facilities at ports. Lifting costs are minor, and much of shale producers’ daily operating costs stem from pipeline rates. Under the present circumstances, when little to no other oil will compete for the American market, shutting in may incur higher costs for producers than simply letting things run normally.

Furthermore, even though the U.S. brokered the historic OPEC+ deal, it lacks the legal tools to force its own states to implement oil cuts. The federal government doesn’t have a state-owned company, and its regulations are not as centralized as those of Russia or Saudi Arabia. It is instead up to the states and the companies themselves whether to cut.

At the same time, U.S. producers are very responsive to price changes, which means shale producers will keep production going only as long as it is profitable for them to do so. And with prices continuing to slide despite the OPEC+ deal, that won’t be long. On April 10, Trump asked the U.S. Department of Energy to purchase crude oil for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which will boost prices temporarily. But eventually companies will close down production because of low prices — something Washington can pass off as a “cut” to the OPEC+ countries.

The Saudi announcement on price differentiation between American and Asian markets means that, in spite of the OPEC+ agreement, Riyadh will effectively intensify its price war in Eurasia. Whatever Saudi output is not sent to the Gulf of Mexico will be sent to Asia, where Saudi Arabia competes with Russia (and others, to a lesser extent, including Iran, Nigeria and Iraq). Though Saudi Arabia knows that Russia will break the agreement — as it has before — it also knows that Saudi oil has only limited time to gain profits.

The global storage capacity is estimated to be between 900 million and 1.8 billion barrels. This is equal to roughly 9-18 days of global supply based on output in 2018, when the world produced nearly 95 million bpd. Assuming that 10 million bpd is put into storage, facilities would be filled in between 90 and 180 days. Since early April reports have been coming in that the United States’ Caribbean and Cushing storage hubs are nearing capacity. The math suggests this will soon be true for the rest of the world. Saudi Arabia, as well as Russia and other producers, is interested in selling as much oil as it can until storage capacity is reached. At that point, the production price of oil will fall close to or even below zero if the coronavirus crisis hasn’t abated and the world is still effectively quarantined.

Even assuming that all producers stick to the OPEC+ plan, if we take the median of the estimate of global storage capacity — 1.35 billion barrels — then the world’s stocks of oil storage will be full by early June. If the deal collapses, and everyone maximizes output, then production prices will fall to single digits or even zero earlier, potentially by mid-May. This reality can be avoided only if the coronavirus outbreak is quickly contained and the global workforce is able to get back to work.

About the author:

Dr. Antonia Colibasanu is Geopolitical Futures’ Chief Operating Officer. She is responsible for overseeing all departments and marketing operations for the company. Dr. Colibasanu joined Geopolitical Futures as a senior analyst in 2016 and frequently speaks on international economics and security topics in Europe. She is also lecturer on international relations at the Romanian National University of Political Studies and Public Administration and associate professor for the Romanian National Defense University Carol I Regional Department of Defense Resources Management Studies. Prior to Geopolitical Futures, Dr. Colibasanu spent more than 10 years with Stratfor in various positions, including as partner for Europe and vice president for international marketing. Prior to joining Stratfor in 2006, Dr. Colibasanu held a variety of roles with the World Trade Center Association in Bucharest. Dr. Colibasanu holds a Doctorate in International Business and Economics from Bucharest’s Academy of Economic Studies, where her thesis focused on country risk analysis and investment decision-making processes within transnational companies. She also holds a Master’s degree in International Project Management. She is an alumna of the International Institute on Politics and Economics at Georgetown University.

Copyright 2020 Geopolitical Futures, LLC. Republished with permission.

Ljubljana/Bucharest, 9 May 2020

Footnotes:

[1] IFIMES - The International Institute for Middle-East and Balkan Studies, based in Ljubljana, Slovenia, has a special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council ECOSOC/UN since 2018.